Can scientists develop an icy sanctuary for Arctic life?

The ambitious goal would preserve summer sea ice, and the creatures that depend on it

Scientists are pinning their hopes on building a sanctuary for Arctic species in the Last Ice Area (seen here), the region of the Arctic where summer sea ice will last longest.

Robert Newton/Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

By Freda Kreier

Polar bears have been struggling in a warming Arctic. But it’s not the first time the iconic species has suffered this fate. In 2012, DNA revealed that polar bears had faced extinction once before. It likely happened during a warm period 130,000 years ago. Afterward, the bears rebounded. For researchers, that discovery led to one burning question: Could polar bears make a comeback again? Such findings now bolster an ambitious plan.

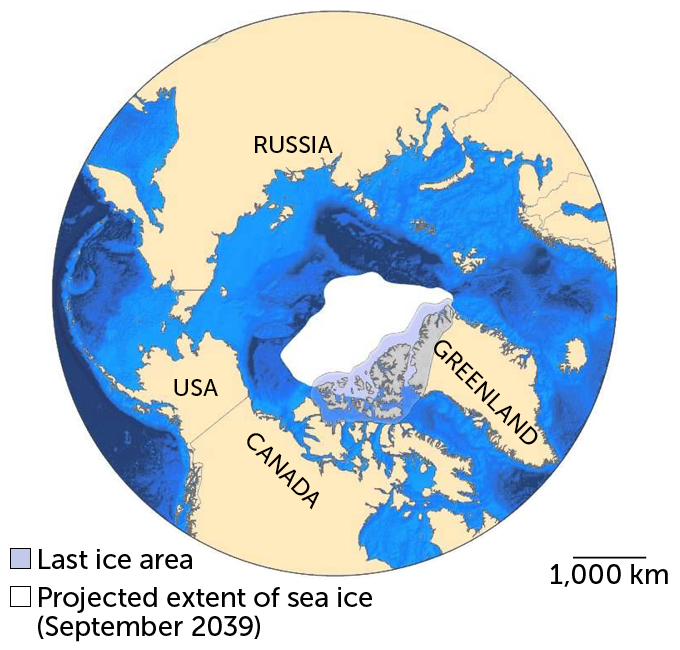

Scientists have proposed creating a refuge for ice-dependent Arctic species. It’s where the Arctic will take its last stand. The proposed site is a part of the Arctic that some call the Last Ice Area. Its ice will continue to exist in the summer even as the planet gets warmer — at least for a few more decades. Here, everything from marine mammals to microbes could hunker down in hopes of riding out climate change.

But how long the Last Ice Area will hold on to its summer sea ice remains unclear.

A computer model released in September predicts that the Last Ice Area could retain its summer sea ice indefinitely — at least if emissions from fossil fuels don’t warm the planet more than 2 degrees Celsius (3.4 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels. That was a goal set by the 2015 Paris climate treaty. But a recent report by the United Nations found that under current pledges by governments to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, Earth’s climate is set to warm 2.7 degrees Celsius by 2100. If true, that would spell an end to the Arctic’s summer sea ice.

Some scientists still hope humankind will curb emissions and roll out new technologies to capture carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. In the meantime, the Last Ice Area could buy time for species that rely on ice. It might serve as a sanctuary until they might one day again stage a comeback.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Life within the frozen sea

The Last Ice Area is a vast floating landscape of solid ice. It spans from the northern coast of Greenland in the east to Canada’s Banks Island in the west. This area, roughly the length of the West Coast of the United States, is home to the oldest and thickest ice in the Arctic. Why? An archipelago of islands in Canada’s far north prevents this ice from drifting south to where the Atlantic would melt it.

As ice from others part of the Arctic rams into this natural barrier, it piles up. Long, towering ice ridges form that run for kilometers (miles) across the frozen landscape. “It’s a pretty quiet place,” says Robert Newton. He’s an oceanographer at Columbia University in New York City. He also is an author of the recent sea-ice computer model, described September 8 in Earth’s Future.

“A lot of the life is on the bottom of the ice,” he says. Its muddy underbelly is home to plankton and single-celled algae that evolved to grow directly on ice. These species form the base of an ecosystem. It feeds everything from tiny crustaceans to beluga whales and polar bears.

These plankton and algal species can’t survive without ice. So as summer sea ice disappears across the Arctic, the base of this ecosystem has been literally melting away.

Before long, much of the habitat these species depend on “will become uninhabitable,” says Brandon Laforest. He’s an Arctic expert at World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Canada in Montreal. With nowhere else to go, he says, these species are “literally being squeezed into the Last Ice Area.”

This stronghold of summer ice provides an opportunity to create a floating sanctuary an Arctic ark, if you will. For more than a decade, WWF Canada worked with a group of researchers and Indigenous communities. Together, they lobbied for the area to be protected from another threat: development by companies that want the region’s oil and mineral resources.

“The tragedy,” Newton says, would be if there was an area where these animals could survive, “but they don’t because it’s been developed commercially.”

But for Laforest, protecting the Last Ice Area is not only a question of safeguarding Arctic life. Sea ice also is an important tool in regulating climate. Its white surface reflects sunlight back into space. This helps cool the planet. In a vicious cycle, losing sea ice speeds the air and water’s warming, which in turn melts more ice.

And for people who call the Arctic home, sea ice is crucial for food security, transportation and cultural survival.

In 2019, the Canadian government set aside nearly a third of the Last Ice Area as protected spaces called marine preserves. For another two years, all commercial activity within the boundaries of the preserves is forbidden. Conservationists are now asking for marine preserves to get permanent protection.

Hope that it’s not too late

Some troubling signs have emerged that sea ice even here is already at risk. Most worrisome was the appearance in May 2020 of a rift in this ice. It was the size of Rhode Island and right in the heart of the Last Ice Area. Kent Moore is a geophysicist at the University of Toronto in Canada. He says that these unusual events may happen more often as the ice thins. This suggests that the Last Ice Area may not be as rugged as we thought, he says.

This worries Laforest, too. He and others are not sure that reversing climate change and repopulating the Arctic with ice-dependent species will be possible. “I would love to live in a world where we eventually reverse warming and promote sea-ice regeneration,” he says. But that seems “a daunting task,” he says.

Others remain hopeful. “All the [computer] models show that if you were to bring temperatures back down, sea ice will revert to its historical pattern within several years,” says Newton.

To save the last sea ice — and the creatures that depend on it — removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere will be essential, says Stephanie Pfirman. She’s an oceanographer at Arizona State University in Tempe. She also is a coauthor of the study on sea ice that Newton worked on. Technology to capture carbon dioxide and to keep more carbon from entering the air, exist. The largest carbon-capture plant is in Iceland. But projects like that one have yet to be started on a major scale.

Without such efforts, the Arctic is set to lose the last of its summer ice before the end of this century. It would mean the end of life on the ice. But Pfirman says that humanity has undergone big economic and social changes in the past — ones on a scale like those that will be needed to reduce emissions and prevent warming.

Protecting the Last Ice Area is about buying time. The longer we can hold on to summer sea ice, says Pfirman, the better chance we have at bringing arctic species — from plankton to polar bears — back from the brink of extinction.