Baby pterosaurs may have been able to fly right after hatching

Fossils show that a bone crucial for lift-off was stronger in hatchlings than in adults

In this artist’s rendition, pterosaurs (Pterodaustro guinazui) fly in Argentina during the Early Cretaceous period. New research suggests P. guinazui babies could fly the moment they hatched.

Mark Witton

Baby pterosaurs may have been able to fly right after hatching. But these ancient reptile babies might have flown a bit differently than adults.

Scientists learned about this ability for super-early pterosaur (TAIR-oh-soar) flight by looking at fossils of their wing bones. The researchers compared these bones in pterosaur embryos, babies and adults. The bones suggest that babies were strong and nimble fliers from the start. Researchers shared their new findings July 22 in Scientific Reports.

Pterosaurs were a diverse group of ancient flying reptiles that lived among the dinosaurs. They emerged about 228 million years ago and died off 66 million years ago. There’s still a lot scientists don’t know about the early development of these winged beings. Among them: whether young ones could actively flap their wings or only glide. If they were gliders, their parents would have had to care for the babies until they were flight-ready.

Researchers have recently uncovered hints that young pterosaurs flew. One group found winglike membranes on the limbs of a pterosaur embryo. Another team discovered a tiny pterosaur that could travel long distances before reaching adulthood.

“Baby pterosaurs almost certainly didn’t glide,” they flew, says Kevin Padian. He’s a paleontologist at the University of California, Berkeley. He was not part of the new study.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

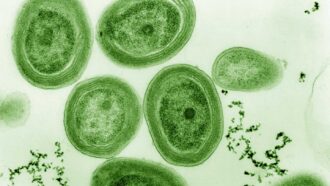

The latest evidence for baby pterosaur flight comes from a team led by Darren Naish. He’s a paleontologist. He works at the University of Southampton in England. Naish’s group compared the fossilized wing bones of pterosaur at all ages — from embryos through adults. The fossils came from two species. One was Pterodaustro guinazui. The other was Sinopterus dongi.

From those fossils, the researchers measured the wingspans and gauged their bone strength. They also figured out how much weight the wings could carry. The team paid special attention to one wing bone: the humerus. This bone is found on the limbs that pterosaurs used to launch themselves into flight. Details of that bone help reveal whether a pterosaur could get off the ground.

The findings were surprising. The humerus bones were stronger in hatchlings than in many adults. The hatchlings also had relatively shorter and broader wings than adults. That means young pterosaurs might have been able to nimbly change direction and speed. But they may not have been able to go long distances.

Agile flying may have helped hatchlings escape predators. It might also have helped them chase tricky prey, such as insects. It might even have helped them navigate dense vegetation. Adult pterosaurs might have been less agile because they were bigger. So perhaps they switched to more open habitats.

Almost no modern birds can fly right after hatching. One notable exception is the maleo. This strange chickenlike bird lives only on the Indonesian islands of Sulawesi and Buton. Taking flight right away helps the maleo avoid predators. They might otherwise by snapped up by monitor lizards and pythons.

But it isn’t unusual for most young animals to fend for themselves, Padian says. Only animals with extended parental care — like songbirds or primates — can afford to be helpless for long.