Check out the communities of bacteria living on your tongue

Mapping which are neighbors could uncover what they need to stay healthy

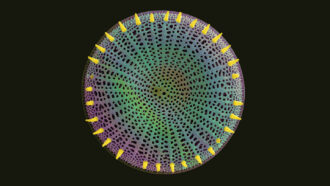

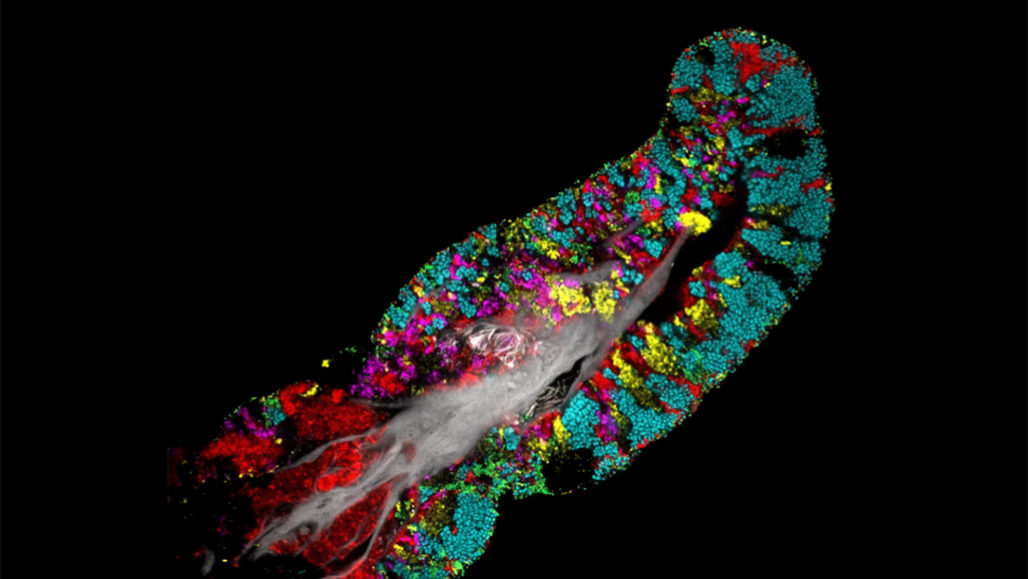

Bacteria that live on the human tongue (different types labeled with different colors) form a thick film around a tongue cell (gray structure at center).

S. Wilbert et al/Cell Reports 2020

Lots of microbes live on human tongues. They’re not all alike, however. They belong to many different species. Now scientists have seen what the neighborhoods of these germs look like. The microbes don’t randomly settle on the tongue. They seem to have chosen particular sites. Knowing where each type tends to live on the tongue could help researchers learn how the microbes cooperate. Scientists might also use this information to learn how such germs keep their hosts — us — healthy.

Bacteria can grow in thick films, called biofilms. Their slimy covering helps the tiny beings stick together and hold on against forces that might attempt to wash them away. One example of a biofilm is the plaque that grows on teeth.

Researchers have now photographed bacteria that live on the tongue. They turned up different types that clustered in patches around individual cells on the tongue’s surface. Just as a quilt is made from patches of fabric, the tongue is covered with different patches of bacteria. But within each small patch, the bacteria are all the same.

“It’s amazing, the complexity of the community that they build right there on your tongue,” says Jessica Mark Welch. She is a microbiologist at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass.

Her team shared its discovery March 24 in Cell Reports.

Scientists usually hunt for fingerprints from DNA to find different types of bacteria. This helps experts uncover what types are present, such as on the tongue. But that method won’t map which live next to one another, Mark Welch says.

So she and her colleagues had people scrape the top of their tongues with a piece of plastic. What came off was a “frighteningly large amount of white-ish material,” Mark Welch recalls.

The researchers then labeled the germs with materials that glow when lit with a particular type of light. They used a microscope to make photos of the now-colored germs from the tongue gunk. Those colors helped the team see what bacteria lived next to each other.

The microbes are mostly grouped into a biofilm that is jam-packed with different types of bacteria. Each film covered a cell on the tongue’s surface. The bacteria in the film grow in groups. Together, they look like a patchwork quilt. But the sampled microbial quilt looked slightly different from one person to another. They also could vary from one area to another. Sometimes a particular colored patch was larger or smaller or showed up at some other site. In some samples, certain bacteria were simply absent.

These patterns suggest that single bacterial cells first attach to the surface of a tongue cell. The microbes then grow in layers of different species.

Over time, they form large clusters. By doing this, the bacteria create miniature ecosystems. And the different residents recruited to the community — the different species — point to the features that a vibrant microbial community needs to thrive.

The researchers found three types of bacteria in nearly everyone. These types tended to live at roughly the same place around tongue cells. One type, called Actinomyces (Ak-tin-oh-MY-sees), usually live close to the human cell at the center of the structure. Another type, called Rothia, lived in large patches toward the outside of the biofilm. A third kind, called Streptococcus (Strep-toh-KOK-us), formed a thin outer layer.

Mapping where they live can point to what’s needed to support a healthy and beneficial ecosystem of these germs in our mouths. For example, Actinomyces and Rothia may be important for turning a chemical called nitrate into nitric oxide. Nitrate is found in leafy green vegetables. Nitric oxide helps blood vessels stay open and to control blood pressure.