Bee Disease

Scientists may have found one reason why honeybees have been disappearing from the United States.

By Emily Sohn

Honeybees are disappearing for unknown reasons around the United States (See “Where Have All the Bees Gone?”).

The decline has been drastic: Last winter, bees disappeared from 23 percent of American beekeeping businesses. The causes, however, have remained a mystery.

Now, scientists from several universities and the U.S. Department of Agriculture say they have a possible explanation for this so-called colony-collapse disorder. The suspect is a little-known virus known as Israeli acute-paralysis virus (IAPV).

|

|

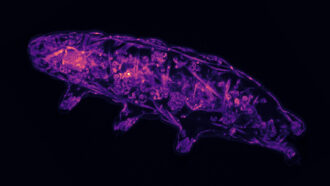

Honeybees in the United States have been plagued by the varroa mite, which you can see here as the dark, rounded parasite on this bee’s back. The mites spread and worsen diseases, possibly including Israeli acute-paralysis virus.

|

| USDA |

The virus kills bees. Researchers in Israel first described it in 2004. But until now, bee experts hadn’t paid much attention to it.

When trying to find out why the bees were disappearing, a research team at Columbia University in New York City studied bee colonies both with and without symptoms of the collapse disorder. In each colony, the scientists looked for germs present only in the sick colonies.

Their search turned up large numbers of two types of fungi. Both had once been suspected of causing colony-collapse disorder. These data, however, showed that the fungi were almost as common in sick colonies as in ones with no symptoms. The researchers concluded that the two fungi probably weren’t responsible.

Studies of IAPV, however, were more revealing. In those studies, done by a team at Pennsylvania State University in University Park, the virus showed up in 83 percent of samples from colonies with symptoms. Only 5 percent of samples from symptomless colonies had it, reports lead researcher Diana Cox-Foster.

Scientists still don’t know whether IAPV can single-handedly cause colony-collapse disorder. One reason is that even if the virus is making colonies sick, it could have a partner in crime. It’s possible, for instance, that mites or chemicals in the environment weaken bees, making them more likely to catch IAPV.

Either way, scientists are encouraged. They now know that the presence of IAPV is a strong sign that a colony has the disorder. And they know how to screen colonies for IAPV.

Scientists are still trying to figure out how IAPV came to the United States. Cox-Foster and her colleagues have found IAPV in living bees from Australia and in bee food from China.

“This is the first record of the virus in North America,” Cox-Foster says.

The United States currently allows bee products to be imported from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. If it turns out that this trade is spreading disease, the rules might eventually change.

Going Deeper:

Milius, Susan. 2007. Hive scourge? Virus linked to recent honeybee die-off. Science News 172(Sept. 8):147. Available at http://www.sciencenews.org/articles/20070908/fob1.asp .

Cutraro, Jennifer. 2007. Where have all the bees gone? Science News for Kids (June 13). Available at http://www.sciencenewsforkids.org/articles/20070613/Feature1.asp .

Milius, Susan. 2007. Not-so-elementary bee mystery. Science News 172(July 28):56-58. Available at http://www.sciencenews.org/articles/20070728/bob9.asp .