To figure out your dog’s ‘real’ age, you’ll need a calculator

You could multiply your dog’s age in human years by seven — but then you’d be wrong

Young or old, they’re all very good dogs. But how old is an old dog? A new finding says the math is more complex than you think.

Jennifer_Sharp/iStock/Getty Images Plus

How old is your dog? Maybe it was born four years ago. At that age, a human would still be a kid. Your dog, however, acts like an adult. You might have heard that to get a dog’s “biological” age, just multiply its age in years by seven. That would make your dog equivalent to a 28-year-old human. But that would probably be wrong, a new study shows. Your dog’s actually more like a 53-year-old human.

Multiplying a dog’s age by seven doesn’t really work, says Matteo Pellegrini at the University of California, Los Angeles. He studies bioinformatics — a research field that uses computers to analyze biological data. He was not involved in the study. On the surface, he notes, multiplying by seven makes sense. On average, people live seven times longer than a dog. So, he notes, “It’s just dividing the human lifespan by the dog lifespan.”

But there are problems with that simple computation. After all, a one-year-old baby is just learning to walk. A one-year-old dog is adult enough to have puppies of its own. This is because species develop at very different rates. Aging doesn’t even happen at the same pace over an individual’s life. “When you’re a newborn, your body is changing very quickly,” Pellegrini explains. “It slows down over time.”

Fortunately, dogs and humans both hit very similar developmental milestones. We’re babies (or puppies), then kids (or, er, still puppies), then adolescents and then adults. As we go through those stages, our DNA also undergoes a change. The molecule that carries genetic instructions stays the same. But over time, this DNA acquires or loses tiny chemical “tags.” These are called epigenetic changes. The tags, known as methyl groups, act like little switches that can turn on or off particular genes in that DNA.

The genome is the complete set of the genes present in an organism’s DNA. “Think of taking a … marker and start drawing in different places in the genome,” says Elaine Ostrander. She studies genetics at the National Human Genome Research Institute in Bethesda, Md. The marks determine how different genes in the DNA get used to make proteins. A complete set of the methyl marks on DNA is called a methylome (METH-el-ohm).

As an animal ages, so does its methylome. How it changes is very predictable. Most adolescent humans will have DNA marks that are in one pattern, while humans nearing 65 or 70 show a different pattern of DNA marks. The same is true for dogs. If the epigenetic markings of humans and dogs at different ages were compared against one another, would there be “places that were kept getting marked up in the same way?” Ostrander and her colleagues wondered. If there were, would finding that pattern in one species point to an equivalent age in the other? Comparing patterns that way might allow people to get at the “real” age of a dog.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

To test this, her team looked at the methylomes from 104 purebred Labrador retrievers. Her team has been collecting DNA samples from dogs around the United States since 1993. “I picked Labs because they can live a long time [for dogs], and we were able to pull [the DNA] out of the freezer,” Ostrander says. “We were able to take DNA samples from Labs that were anywhere from a few months old to 16 or 17 years old.” The researchers compared the dog methylomes to methylomes of 320 people between the ages of 1 and 103.

And it worked. By comparing the patterns, they scientists found they could figure out how dog years relate to human years.

Age isn’t just a number

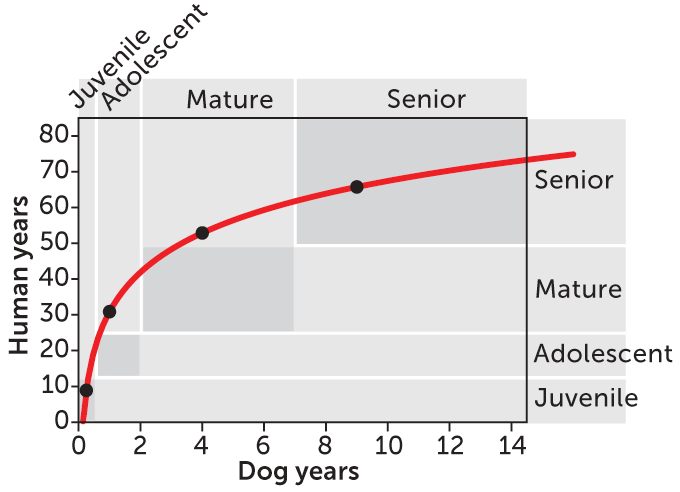

How an age in years corresponds to a species’ biological age changed over time, they found. “You don’t see a … straight line,” Ostrander says. “What we see is this curve that levels out as humans get old and dogs get old.”

Early in life, puppies develop much faster than people do. But as dogs get older, their aging curve begins to flatten. The scientists took this curve and developed a new mathematical equation to calculate a dog’s age. Sadly, it’s not as easy as multiplying by seven (that would just give you a straight line, not a curve). Ostrander and her colleagues published their new formula online July 2 in Cell Systems.

The new formula relies on the mathematical concept known as logarithms. And not just any logarithms, but those known as “natural” ones. To figure out a dog’s biological age, they say, multiply the natural logarithm of the dog’s age in years by 16. Then add 31.

Dog days

This graph compares Labrador retrievers at different ages with humans at different ages. It’s based on chemical tags on DNA and how they change over time in both species. It shows a 1-year-old dog is biologically closer to a 31 year-old human (second dot from left). A 4-year-old dog is like a 53-year-old human (third dot).

Such an operation is probably not math you can do in your head. (That’s okay, there’s an “ln” function on most calculators.) With this new formula, an 8-week-old puppy is roughly the same developmental age as a 9-month-old baby. A year-old dog corresponds to a 31-year-old adult human. And the 4-year-old dog from the beginning of the story is about comparable to a 53-year-old human. The new formula also lines up the average life span of a Lab (12 years) with the average 70-year human life span.

“I think it’s very cool they looked at the DNA methylation [patterns] and they compared them to match up the relative ages,” says Pellegrini. Other researchers will of course have to confirm the new findings, he adds.

And then there’s the issue of breed. The new study only used Labs. “There’s a big difference in longevity across dog breeds,” he notes. Smaller dogs, such as chihuahuas, can live close to 20 years. St. Bernards and other very large dogs might only live 10. Scientists will have to look at the methylomes of different dog breeds to see if they differ. They’re just going to have to study many more very good dogs.