A ‘ghost’ gene leaves sea mammals vulnerable to some toxic chemicals

Evolution left marine mammals unable to produce a pesticide-busting protein

The ancestors of manatees and other marine mammals shed certain genes millions of years ago. One of those genes protects against certain harmful pesticides.

Robert K. Bonde/USGS–Gainesville

Creatures deal with toxic chemicals in their environments in many ways. One strategy: Destroy them with chemical-busting proteins. Many mammals have a gene that helps them break down certain toxic chemicals. But sea-dwelling mammals have a dud version of this gene, new research shows. And without it, manatees, dolphins and other marine mammals appear vulnerable to dangerous pesticides.

The gene is called PON1. It carries instructions for making a protein that interacts with fatty molecules in the blood. But that protein has taken on another role in recent decades. It helps break down harmful chemicals found in a class of common pesticides. These chemicals are called organophosphates (Ohr-GAN-oh-FOSS-faytz). Farmers spray them onto many crops to fend off hungry insects.

But those chemicals don’t always stay put, notes Wynn Meyer. She studies evolution and genetics at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. Rains wash these pesticides off of farm fields and into rivers and streams, she says. From there, they can pollute waterways and coastal areas.

That risks poisoning wildlife. But PON1 may offer a defense. It might help break down chemicals that get into animals’ bodies. Meyer and her colleagues wanted to know whether differences in the PON1 gene affected how animals dealt with pesticides.

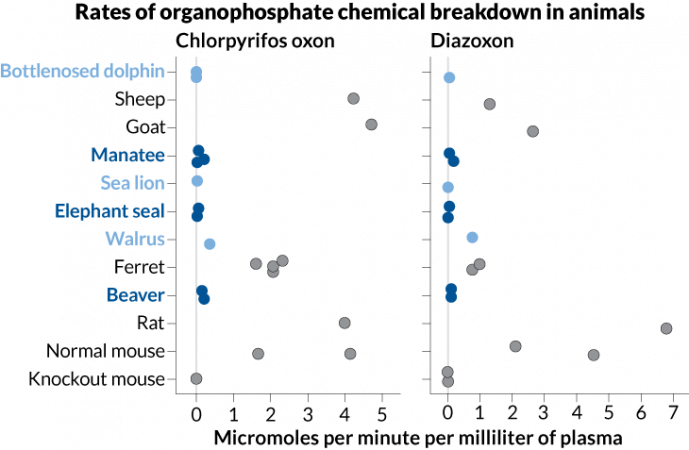

First, they looked at the genes of 53 species of land mammals. All had a working form of PON1. And in lab tests, blood from five of the species — including sheep, goats and mice — could break down two pesticides. When mixed with blood from one of these species, the amount of the toxic chemicals dropped over time. Something in the blood — possibly PON1 proteins — was breaking them down.

The same was not true for aquatic mammals. In five tested species, the PON1 gene contained lots of changes, known as mutations. Those changes had turned off the gene, Meyer says. And sure enough, the sea animals’ blood had little to no effect on the toxic chemicals. That suggests marine mammals can’t get rid of organophosphate pesticides.

Mice genetically altered to lack PON1 couldn’t break down the chemicals either.

Meyer and her colleagues reported their findings Aug. 10 in Science.

Story continues below graph.

Defunct defenses

The researchers compared PON1 genes in more than 60 species of mammals. They estimate that the gene went defunct in sea-dwelling species about 64 million to 21 million years ago. That means it happened after marine mammals’ ancestors moved from land to the sea. Changes in diet or behavior related to that move might have made the gene unnecessary, the researchers suspect.

A busted PON1 gene may not mean marine mammals are helpless against organophosphates, says Andrew Whitehead. He works at the University of California, Davis, and was not involved in the new work. But Whitehead does study how genes change in response to the environment. Marine mammals might have other ways to cope with the chemicals, he says. Yet the new study does seem to find “they aren’t stepping up to the plate.”

What happens to pesticides that don’t get broken down? Some can build up in an animal’s body. DDT is a different pesticide that lingers in the environment. It builds up in animals’ tissues once they swallow it. DDT-poisoned birds lay eggs with fragile shells that break before hatching. And in marine mammals, high levels of DDT damage the nervous system and can cause birth defects. That’s why the United States and dozens of other countries have banned use of DDT.

It’s unclear if organophosphates build up in marine mammals’ bodies in a similar way. But even if they don’t, they may still cause problems.

“Organophosphates don’t stick around as long in the environment as DDT,” Whitehead says. But the chemicals are still used on crops and to kill mosquitoes and other pests. So there’s always more entering the environment.

The researchers next want to study animals in coastal areas that have chemical runoff from farms, says study coauthor Nathan Clark. He is an evolutionary biologist also at the University of Pittsburgh. They plan to collect blood samples from dolphins and manatees in those waters. They will look for evidence that the animals have been exposed to the pesticides. If so, that will help scientists look for links between chemicals in the environment and effects in animals’ bodies, he says.