Milky Way’s tidal forces are shredding a nearby star cluster

Affected stars are moving so fast this cluster could be ‘dead’ in just 30 million years

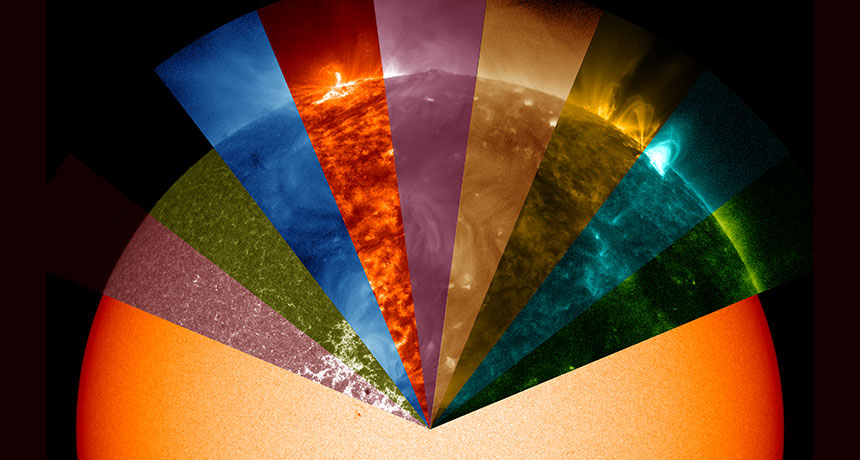

The 680-million-year-old Hyades star cluster (shown) has just 30 million years left to live, researchers say. The brilliant orange star at left, named Aldebaran, does not belong to the cluster.

NASA, ESA, STScI

By Ken Croswell

The cluster of stars closest to Earth is falling apart and will soon die. Astronomers shared the diagnosis based on data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia space observatory.

Called the Hyades, this star cluster is a mere 150 light-years away from Earth. It formed some 680 million years ago from a large cloud of gas and dust in the Milky Way. It’s visible to the unaided eye in the constellation Taurus.

Launched in December 2013, Gaia’s job is to make a three-dimensional map of the Milky Way. It is charting the positions of a billion stars. It is also measuring the velocities of stars. Among these include many of the stars in and around the Hyades cluster.

Stellar gatherings such as the Hyades are known as open star clusters. They are born with hundreds or thousands of stars. The group is held together by the gravitational pull of its stars. But many forces try to tear apart these star clusters. For instance, there are supernova explosions. These occur when the most massive stars die; they eject material that had been holding the cluster together. Large clouds of gas may also pass near the cluster, yanking away some of its stars. Even the cluster’s home stars interact in ways that may serve to push out the least massive ones. Finally, the gravitational pull of the whole Milky Way galaxy can lure away some stars.

In the end, open star clusters rarely reach their billionth birthday. The new work finds the Hyades, too, is doomed. “We find that there’s only something like 30 million years left,” says Semyeong Oh. She’s an astronomer in England at the University of Cambridge. “Compared to the Hyades’ age,” she notes, “that’s very short.”

Oh and N. Wyn Evans, a Cambridge colleague, posted their findings July 6 at arXiv.org.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Speedy escapes

To better understand the Hyades cluster, Oh and Evans compared the speed of stars smack in the center to those escaping from it. From this, they have predicted the cluster’s demise.

The Hyades has survived longer than many other open star clusters. But astronomers saw signs of trouble here in 2018. That’s when teams in Germany and Austria each used Gaia to show many stars already had left the cluster. The cluster is about 65 light-years across. The departing stars form two long tails — each hundreds of light-years long — streaming out of opposite sides of the cluster. These were the first such tails ever seen near an open star cluster.

On the move

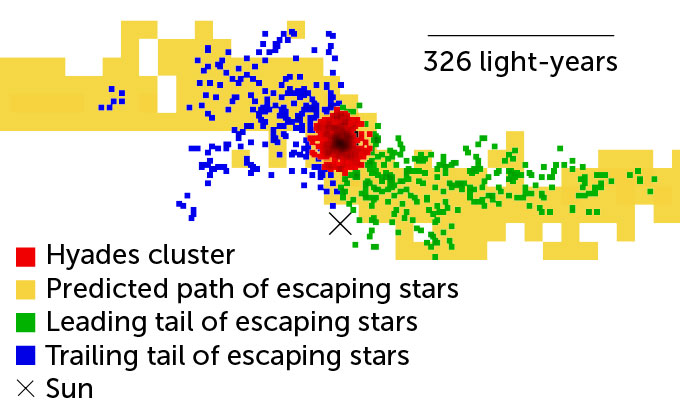

The Hyades star cluster (shown in red) had long been suspected of losing stars in two tails (yellow). Astronomers first spotted the escaping stars in 2018. Some of the escaping stars (green) lead and other stars trail (blue) the cluster as it revolves around the Milky Way’s center.

The Hyades’ stellar tails

In the new work, Oh and Evans analyzed how the cluster has lost stars over its life. It had been born with a mass about 1,200 times that of our sun. Today only 300 solar masses remain. In fact, the two tails of escapees possess more stars than does the cluster.

The more stars the cluster loses, the less gravity it has to hold on to its remaining members. This means even more stars can escape, quickening the cluster’s demise.

Siegfried Röser is an astronomer at Heidelberg University in Germany who led one of the two teams that two years ago discovered the cluster’s tails. He agrees that the Hyades is in its sunset years. But, he says, it’s too soon to set a precise date for its funeral. “That seems to be a little bit risky to say,” Röser says. Running a computer model with the stars’ masses, positions and velocities should better predict what’s in store, he says.

Oh says the main culprit behind the upcoming death of the Hyades is the Milky Way. Just as the moon causes tides on Earth, lifting the seas on both the side facing the moon and the side facing away from it, so the galaxy exerts tides on the Hyades: The Milky Way pulls stars out of the side of the cluster that faces the galactic center as well as from the cluster’s far side.

But even millions of years after the cluster has broken up, its stars will continue to drift through space. Just like parachutists jumping out of the same airplane, they’ll move with similar velocities. “It’s still probably going to be detectable as a coherent structure,” Oh says, even as it gets more strung out.