Mars appears to have a lake of liquid water

The site, beneath the Red Planet’s southern ice sheets, may be the best place to find extraterrestrial life

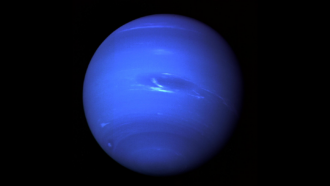

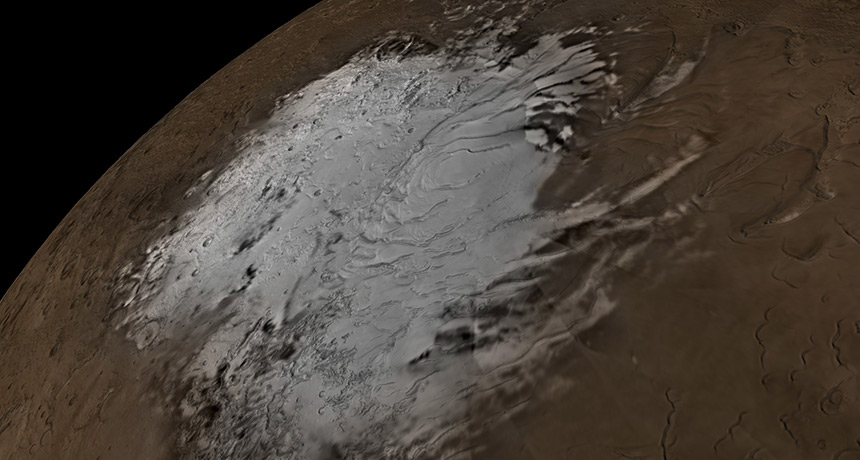

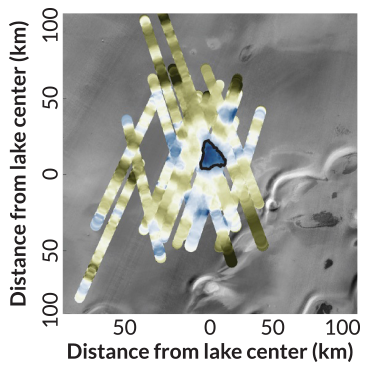

There may be a 20-kilometer-wide lake hidden under Mars’ southern polar ice sheets. Those ice sheet are shown here in images from a camera on NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor spacecraft.

Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio Mars Orbiter Camera data/NASA

A Mars orbiter has detected a wide lake of liquid water. That lake lies hidden below the planet’s southern ice sheets. There had been tiny, brief signals of water on the Red Planet before. But if confirmed, this lake marks the first discovery of a long-lasting store of liquid water, not just ice.

“This is potentially a really big deal,” says Briony Horgan. She’s a planetary scientist at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind. “It’s another type of habitat in which life could be living on Mars today,” she explains.

The lake is about 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) across. That’s what planetary scientist Roberto Orosei of the National Institute of Astrophysics in Bologna, Italy and his colleagues reported online July 25 in Science. But the lake is buried under 1.5 kilometers (almost a mile) of solid ice.

Orosei and his colleagues spotted the lake by combining data collected over more than three years. The observations had come from the European Space Agency’s orbiting Mars Express spacecraft. An instrument called MARSIS — which stands for Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding — aimed radar waves at the planet. These were able to peer beneath the ice.

As the radar waves passed through the ice, they bounced off different materials embedded in the glaciers. The brightness of the returning echo told scientists about the material doing the reflecting. Notably, liquid water makes a far brighter echo than either ice or rock.

Orosei’s team combined 29 radar observations. They were made between May 2012 and December 2015. A bright spot emerged in the ice layers near Mars’ south pole. It was surrounded by much less reflective areas. The researchers considered other explanations for the bright spot. Perhaps the radar had bounced off of some carbon dioxide ice at the top or bottom of the sheet, for instance. In the end, the team decided such alternative explanations options wouldn’t produce the same radar signal or were too much of a stretch to be likely.

That left one option: A lake of liquid water.

Lakes have been discovered in the same way beneath the ice in Antarctica and Greenland.

“On Earth, nobody would have been surprised to conclude that this was water,” Orosei says. “But to demonstrate the same on Mars was much more complicated.”

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

A big, cold, salty pool

The lake is probably not pure water. One reason: Temperatures at the bottom of the ice sheet are around –68° Celsius (-90.4° Fahrenheit). At that temperature, pure water would be frozen, even under the pressure of so much ice. But if a lot of salt were dissolved in the water, the freezing point could prove much lower. Salts of sodium, magnesium and calcium have been found elsewhere on Mars. If they were here, too, they might help to keep this lake liquid.

The pool also could be more mud than water. Still, Horgan says, that might be an environment able to support life.

Previously, scientists have discovered extensive sheets of solid water ice under the Martian soils. There also were hints that liquid water once flowed down cliff walls (although those might have been tiny dry avalanches). The Phoenix lander saw what looked like frozen water droplets near Mars’ north pole in 2008. Scientists suspect, however, that the water was melted by the lander itself.

“If this [lake] is confirmed, it’s a substantial change in our understanding of the present-day habitability of Mars,” says Lisa Pratt. She’s NASA’s planetary protection officer. (Such people look to keep spacecraft from contaminating planets with life from elsewhere.)

How deep the newly discovered lake is remains unclear. Still, its volume dwarfs any previous signs of liquid water on Mars, notes Orosei. The lake has to be at least 10 centimeters (4 inches) deep for MARSIS to have noticed it. That means it could contain at least 10 billion liters (2.6 billion gallons) of liquid water. That’s roughly the volume of water contained by 4,000 Olympic size swimming pools.

“That’s big,” Horgan says. “When we’ve talked about water in other places, it’s in dribs and drabs.”

A decades-long hunt

Under-ice lakes on Mars were first suggested in 1987. The MARSIS team has been searching since Mars Express began orbiting the Red Planet in 2003. Sill, it took the team more than a decade to get enough data to convince themselves the lake was real.

For the first several years of observations, limits in the spacecraft’s computer forced the team to average hundreds of radar pulses together before sending those data back to Earth. That tactic sometimes cancelled out the lake’s reflections, Orosei says. The result: On some orbits, the bright spot was visible. On others, it wasn’t.

In the early 2010s, the team switched to a new technique. This one let them store the data, then send it to Earth more slowly. Three years ago, months before the end of the observing campaign, the experiment’s principal investigator died unexpectedly.

“It was incredibly sad,” Orosei says. “We had all the data, but we had no leadership. The team was in disarray.”

To have finally turned up the lake is “a testament to perseverance and longevity,” says Isaac Smith. He’s a planetary scientist in Lakewood, Colo., who works for the Planetary Science Institute. “Long after everyone else gave up looking,” he notes, “this team kept looking.”

Still, there is room for doubt, says Smith. He works on a different radar experiment for NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, or MRO. It has seen no sign of the lake, even in 3-D views of the poles taken with CT-like scans. It could be that MRO’s radar is scattering off the ice in a different way. It’s also possible that the wavelengths it uses don’t penetrate as deeply into the ice. The MRO team will look again. Having a specific spot to aim for is helpful, he says.

“I expect there will be debate,” Smith says. “They’ve done their homework. This paper is well earned.” Still, he adds, “We should do some more follow-up.”