New El Niño coming on strong

Major weather shifts could bring global changes, including extra rain to drought-stricken California

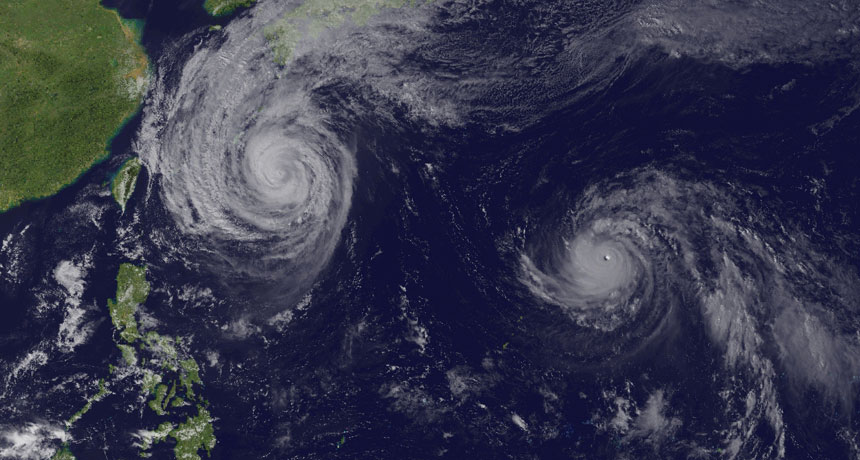

The current El Niño might strengthen typhoons in the Pacific.

Tim Olander and Rick Kohrs, SSEC/CIMSS/UW-Madison, based on Japan Meteorological Agency data

The “little boy” of climate science is making a big splash.

El Niño, Spanish for “the boy,” is a set of major weather changes that happens every few years. It’s caused by unusually warm seawater in the eastern Pacific, off of South America. This year’s El Niño began in March. And it could become a whopper. That’s a July 9 assessment by the Climate Prediction Center of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The agency predicts that this El Niño has a better than 90 percent chance of lasting through the Northern Hemisphere winter. It also has around an 80 percent chance of continuing on through next spring.

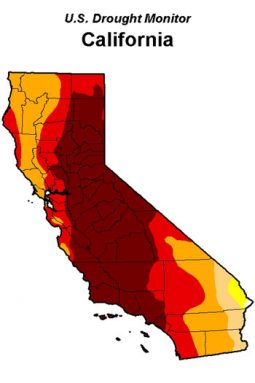

If it proves long-lasting, the 2015 El Niño will change weather around the world. It might cause droughts in the Western Pacific. It could also bring heaps of much-needed rain to California, which is experiencing a state-wide drought. On July 16, the Climate Prediction Center said Californians could expect above-average rainfall in some parts of the state from September through April 2016.

The ongoing El Niño has already reached “moderate” status. It has more than a 50 percent chance of becoming “strong” — the highest level, says Anthony Barnston. A climate scientist, he works at Columbia University in Palisades, N.Y.

With such a powerful start, this year’s event might even prove a record setter. It could compete with the “super El Niños” of 1982 to 1983 and 1997 into 1998, says Kevin Trenberth. He’s a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo. “As far as I can tell,” he said of the El Niño, “it’s currently as large as it’s ever been for this time of year.”

El Niño events happen about every three to five years. Changing wind patterns over the Pacific Ocean push a huge pool of warm seawater eastward toward the Americas. The warmth of this water shifts the flow of heat and moisture around the planet. El Niño years can change storm activity, causing stronger typhoons (hurricanes) in the Pacific and quieter hurricane seasons in the Atlantic. This year’s El Niño is the first since 2010. (Events in 2012 and 2014 fizzled out before they could officially take off.)

The strongest effects from El Niño usually hit each hemisphere in its winter. Countries in the Southern Hemisphere, such as Brazil and Australia, already have seen less rainfall thanks to the current El Niño. The drama will shift northward over the coming months. This might cause droughts in India and southeastern Asia. In the United States, the Ohio Valley, Great Lakes and Pacific Northwest all will probably be drier than normal. And more rain than usual will probably fall on the western Gulf Coast and Southern California.

And even with a strong El Niño, there is no guarantee California will see increased rains, notes Michelle L’Heureux. She’s a climate scientist at that Climate Prediction Center. During the strong 1965 to 1966 El Niño, she points out, less rain than average fell across that state.

Whatever happens in California, El Niño’s impacts might still be felt worldwide. The extra heat released into the atmosphere from the Pacific Ocean can spike global average temperatures, says Tom DiLiberto. He’s a meteorologist at the Climate Prediction Center. If El Niño keeps getting stronger — as it’s expected to — both 2015 and 2016 could easily end up among the hottest years on record, he says. And in future decades, climate change could make strong El Niño events more frequent, bringing extra warmth with them.

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

climate The weather conditions prevailing in an area in general or over a long period.

climate change Long-term, significant change in the climate of Earth. It can happen naturally or in response to human activities, including the burning of fossil fuels and clearing of forests.

drought An extended period of abnormally low rainfall; a shortage of water resulting from this.

El Niño Extended periods when the surface water around the equator in the eastern and central Pacific warms. Scientists declare the arrival of an El Niño when that water warms by at least 0.4 degree Celsius (0.72 degree Fahrenheit) above average for five or more months in a row. El Niños can bring heavy rainfall and flooding to the West Coast of South America. Meanwhile, Australia and Southeast Asia may face a drought and high risk of wildfires. In North America, scientists have linked the arrival of El Niños to unusual weather events — including ice storms, droughts and mudslides.

Great Lakes A system of five interconnected lakes — Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie and Ontario — the Great Lakes constitute the largest freshwater source in the world (based on surface area). They hold an estimated 6 quadrillion gallons of water, or about a fifth of the world’s fresh surface water. To give some perspective on that amount, the lakes’ water would, if spread evenly, cover the 48 touching U.S. states to a depth of about 2.9 meters (9.5 feet) deep.

hurricane A tropical cyclone that occurs in the Atlantic Ocean and has winds of 119 kilometers (74 miles) per hour or greater. When such a storm occurs in the Pacific Ocean, people refer to it as a typhoon.

meteorologist Someone who studies weather and climate events.

National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA A science agency of the U.S. Department of Commerce. Initially established in 1807 under another name (The Survey of the Coast), this agency focuses on understanding and preserving ocean resources, including fisheries, protecting marine mammals (from seals to whales), studying the seafloor and probing the upper atmosphere.

typhoon A tropical cyclone that occurs in the Pacific or Indian oceans and has winds of 119 kilometers (74 miles) per hour or greater. In the Atlantic Ocean, such storm are referred to as hurricanes.