Our sun is neighbor to a giant wave of gas

Lots of stars are being born along this rope of gas called the Radcliffe Wave

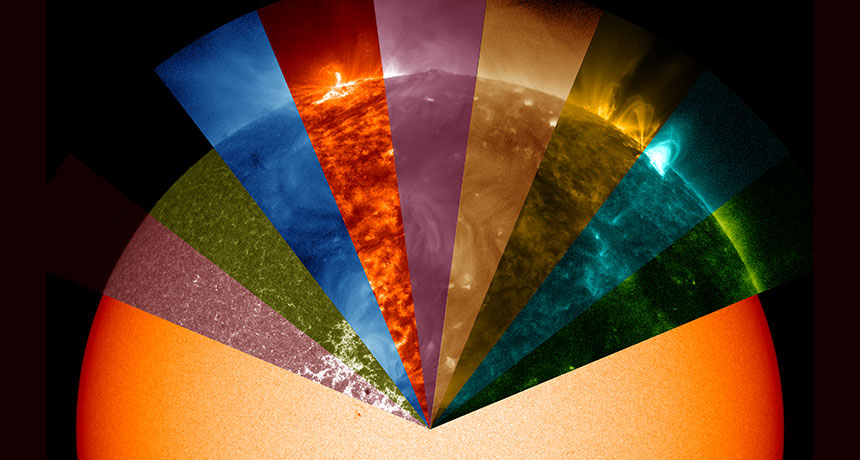

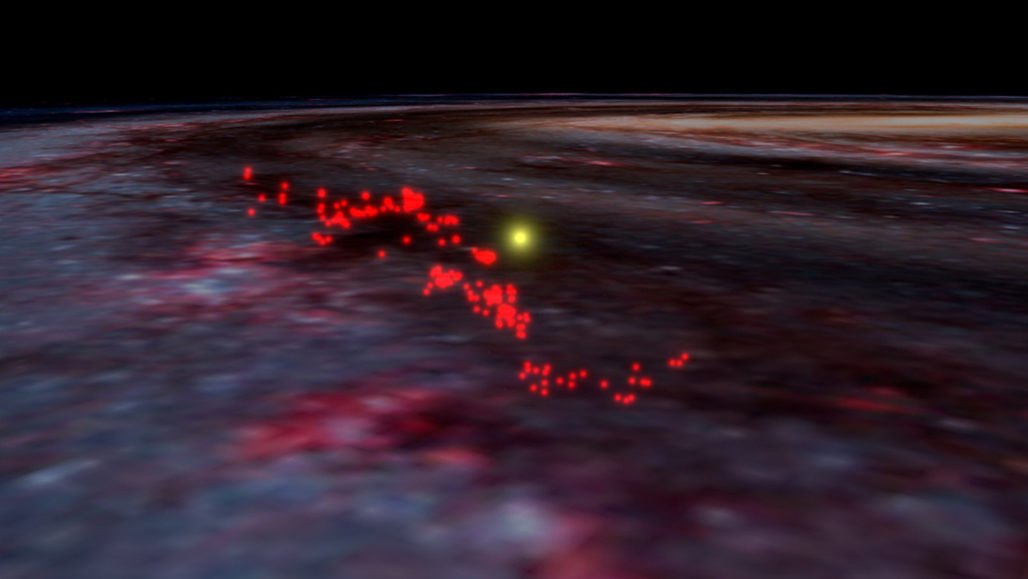

There are many well-known star-forming clouds, shown as red dots in this illustration of the Milky Way. These clouds sit near the sun (yellow). And, it turns out, they actually lie along a wave of star-forming gas newly dubbed the Radcliffe Wave.

WorldWide Telescope, Courtesy of A. Goodman

HONOLULU, Hawaii — The Earth and sun sit right next to a wavy rope of gas. It’s got lots of stars being born in it. But astronomers never noticed it before.

“Perhaps the oddest feature is how close it is to the sun, and we didn’t know about it,” said Alyssa Goodman. She is an astrophysicist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. She described the newfound gas at a news conference on January 7. It took place at a meeting, here, of the American Astronomical Society. The finding also was published the same day in Nature.

Stars are born in gas clouds known as stellar nurseries. There are lots of these nurseries nearby, such as the Orion Nebula. And, it turns out, most are actually stretched along one continuous thread of gas. That gas thread stretches roughly 9,000 light-years, Goodman’s team now reports.

The thread resembles a wave. And the wave soars above and below the disk of our galaxy by about 500 light-years. At one point, it comes within 1,000 light-years of our solar system.

The team dubbed the newly found structure the Radcliffe Wave. Goodman said the team chose this name in honor of the institute where much of the work was done. It was also named for the early 20th century female astronomers from Radcliffe College. The college was a female liberal arts school that eventually became part of Harvard University.

Despite how close the wave is to us, astronomers noticed it only now. And they only noticed it now because of recent advances in the ability to pinpoint distances to known star-forming gas clouds. To nail down those distances, Goodman and her colleagues looked at stars behind the clouds. The team then figured out how dust within those clouds altered the colors of the stars.

The researchers then combined the measurements with distances to those stars. Those data were provided by the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite. The results allowed the team to map in 3-D the locations of the clouds with newfound precision. And that map showed the gas clouds line up along the wave.

“These kinds of waves have been seen in external galaxies,” says Lynn Matthews. She was not involved with this study. An astrophysicist, she works at the MIT Haystack Observatory in Westford, Mass. The new finding “gives us an opportunity to tie together phenomena that have been observed in several galaxies,” she says. It also helps offer “a unifying picture of what might cause these sorts of features,” she adds.

There’s one take-home message from the study. Another involves a structure called Gould’s Belt. Since 1879, astronomers thought this belt was a nearby ring of stars and gas. But its origin has long been debated. The new study shows it never existed. The ring was just an illusion. It was a 2-D projection of the newly discovered wave onto the sky.

“It’s a very careful study,” says Jay Lockman. He is an astrophysicist at Green Bank Observatory in West Virginia. He, too, was not involved with the new research. “What’s interesting about this [new finding],” he says, “is it ties together a lot of very familiar things in the sky that previously had a very different model.”

How the wave formed is unknown. So is what it means for understanding the Milky Way. The wave “could have been from a collision, something falling down on the Milky Way,” Goodman said. Matthews has another idea. She and her colleagues saw something similar in a spiral galaxy known as IC 2233. As a result, she thinks such gas waves might arise from gravitational disturbances. She thinks that such waves could come the interactions of structures within the galaxy.

“The main point is it’s something internal to the galaxy,” Matthews says. If that’s the case, then there’s no need to have a dwarf galaxy or something else colliding with the Milky Way to make such a wave.

Regardless of how it formed, this gas thread might have interacted with the sun before. The astronomers traced the motion of the sun through space backward in time. This revealed that our solar system likely passed right through Radcliffe’s Wave roughly 13 million years ago. And when it did, it would have made the night sky look amazing. It would have been full of bright, beautiful gas clouds, Matthews said. They “would have been a lot closer and a lot easier to see — and possibly all around us.”