Bright-colored feathers may have topped pterosaurs’ heads

These crests likely helped the flying reptiles keep warm and show off to mates

Tupandactylus imperator (illustrated) is a pterosaur that lived about 113 million years ago. A new study of the fossilized specimen of one of these turned up evidence that vibrant feathers topped the flying reptile’s head.

Bob Nicholls

Looking swank may have been a plus for pterosaurs. These ancient flying reptiles sported colorful head feathers, fossil evidence now suggests.

The finding means that feathers could date back to a common ancestor of dinosaurs and pterosaurs. That would mean they first appeared during the early Triassic Period. At 250 million years ago, that’s far earlier than scientists had believed.

Scientists analyzed the partial fossil skull of a 113-million-year-old pterosaur (TAIR-oh-sawr). It shows this reptile had two types of feathers on its head, says paleontologist Aude Cincotta. She works at University College Cork in Ireland. Some feathers were long and thin. They looked like whiskers. Others had a more complex, branching structure. These feathers are more like those on modern birds. Cincotta and her colleagues described their findings April 20 in Nature.

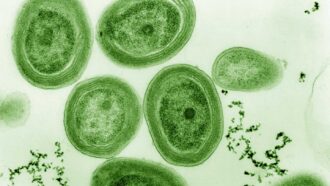

The fossil’s soft tissues (non-bones) were also well-preserved. These allowed the team to identify a variety of different shaped cells containing colored pigments. These cells, called melanosomes (Meh-LAN-uh-soams), showed up in both feathers and skin. The shape of these cells ranged from “very elongate, cigar shapes to flattened platelike disks,” says Maria McNamara. A paleobiologist, she works at University College Cork, too.

Melanosome shapes have been linked to different colors, she points out. Roundish ones usually relate to yellow or reddish-brown colors. The longer-shape ones have been linked to darker colors.

The shapes of the fossil’s melanosomes suggest this creature may have been quite flashy, the team says. This also hints that those feathers weren’t just for warmth. They may have been used to send signals, such as to attract a mate.

Ancient fluffballs

Pterosaurs are a diverse group of prehistoric flying reptiles. They were not dinosaurs but lived amongst them. It’s widely believed they were Earth’s first true vertebrate flyers. But scientists have long debated whether pterosaurs had true feathers. Some experts believe they had more primitive hairlike structures, known as pycnofibers (PIK-no-fy-burz). In either case, they didn’t use feathers to fly. Instead, they used membranes that stretched between their wings. (You see a similar thing in modern bats.)

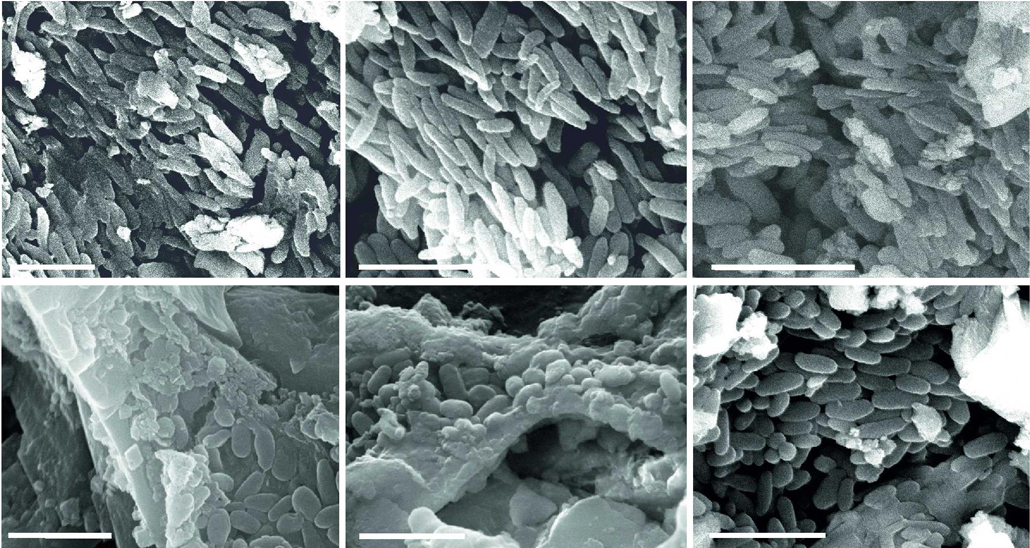

In 2018, McNamara and her colleagues reported that some of the fuzz covering two fossilized pterosaurs clearly showed complex branching patterns that seemed similar to modern feathers. But other researchers argued that the patterns were due to overlapping pycnofibers.

McNamara says the new work has “turned all that on its head.” In this fossil, the branches are all the same length. And they extend all down the feather’s shaft. “It’s very clear. We see feathers that are separated, isolated — you can’t say it’s an overlap of structures.”

The pterosaur fossils described in 2018 did have some preserved melanosomes. But those were “little, short ovoids,” McNamara says. In the new fossil feathers, “for the first time we see melanosomes of different geometries.” That could mean bright, colorful plumage.

“To me, these fossils close the case. Pterosaurs really had feathers,” says Stephen Brusatte. He’s a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. He was not part of the new study. “Not only were many famous dinosaurs actually big fluffballs,” but so were many pterosaurs, he now says.

Some of those feathers were also colorful. This study shows that feathers aren’t just for birds or dinosaurs. Feathers evolved even deeper in time, Brusatte says. And the feathers must have had purposes other than flying. That could have been insulation and communication.

Dinosaurs and pterosaurs might have evolved this colorful plumage independently, McNamara notes. Still, she says, the shared geometries of the pigment cells in both groups of reptiles makes it “much more likely that it was derived from a common ancestor” back in the early Triassic.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

An evolving advantage

“That’s a big new implication,” says paleontologist Michael Benton. He’s at the University of Bristol in England. He also worked with McNamara on the 2018 study. If feathers arose in a common ancestor, he says, that would push back the origin of feathers to roughly 250 million years ago. That’s some 100 million years earlier than scientists had thought!

The early Triassic Period was a hard time on Earth. It followed a mass extinction known as the Great Dying that killed off the vast majority of the planet’s species. Additional insulation from feathers could have helped keep reptiles warm at this time. The evolution of feathers may have been part of a survival struggle between mammal ancestors and some pterosaur-dinosaur ancestor.