Scientists find genes that make some kids’ hair uncombable

Mutations in any of three genes causes a disorder that makes hair impossibly tangled

Think your hair is hard to comb? It’s a piece of cake compared to what a few kids confront every day. They’ve inherited a gene for uncombable hair.

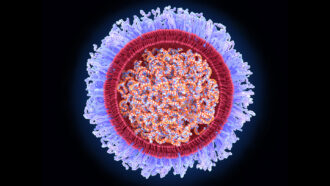

hjalmeida / iStockphoto

By Dinsa Sachan

Lots of kids have heard this refrain: “Brush your hair! It’s a mess!” For most people, combing hair may be, at most, a chore. For an unfortunate few kids, however, every day is a bad hair day. And they can’t help it. These youngsters have a strange — though usually not permanent — condition that makes their snarly hair nearly impossible to tame. Scientists have now pinpointed several genes that appear to be responsible for this “uncombable hair syndrome.”

Yes, that’s it’s official name.

Affected children have frizzy, tangled hair. The abnormality has nothing to do with grooming habits. The hair’s structure is simply different from that in most people. The bad news: Shampoos and conditioners rarely do much to control it.

Normally, a hair strand or shaft (the part of the hair that sticks out of the scalp) looks relatively smooth under a microscope. In kids with uncombable hair syndrome, the shaft instead appears to have grooves along each strand’s length. A cross-section of a single hair shaft (the shape you’d see if you were looking at it from the end) resembles a heart or a kidney. Still, the hair looks somewhat shiny. The good news: Most kids will outgrow this curse of totally unruly hair. By the time they reach their teens, their hair starts to sort itself out.

No one knows how common uncombable hair syndrome is, says Regina Betz. She is an author of the new study who works at the Institute of Human Genetics at the University of Bonn in Germany. Betz is an expert in rare hereditary hair disorders. To date, scientists have reported only about 100 cases worldwide. But there are probably many more, Betz says. “Maybe they didn’t go to the doctor,” she says. “Or the doctor did not recognize that this was uncombable hair syndrome.” That’s not surprising, given how rare the condition is.

Scientists already knew that the syndrome was genetic. After all, if one kid has it, someone else in his or her family generally does too — or did. But no one had any clue about which gene might be to blame. That’s because there had been so few studies on the condition.

When one of Betz’s colleagues told her about a British family with two children having this uncombable hair, she got curious and decided to launch a study. Her team roped in more affected kids from across Europe. First, they analyzed each child’s DNA. That’s our genetic instruction book. They sequenced that DNA, meaning they used a tool to read out the exact order of the individual building blocks in this molecule.

Next the scientists compared those DNA sequences in children with uncombable hair syndrome to those in people whose hair behaves normally. Three genes differed in the kids with uncombable hair. Betz’s team shared published its findings online in the November 2016 American Journal of Human Genetics.

Scientists already knew that these three genes are responsible for making hair strong. They contribute to the structure of a hair’s shaft. But Betz and her colleagues found that if there is a mutation in one of the genes — a change in its DNA — that’s enough to make a child’s hair totally unmanageable.

To find out how the mutations messed with a kid’s hair, Betz’s team did an experiment. In the lab, they grew both normal cells and cells with the mutation. When they did that, they found that the mutations caused the strong-hair genes to make proteins that formed messy clumps. The normal form of the proteins won’t normally do that.

Next, the researchers wanted to find out whether mutations in those genes would lead to uncombable hair in real life. Of course, it would be unethical to mess with people’s genes to find out. Instead, the team used mice. They disabled one of the three suspect genes in some mice. They left the others’ genes alone. The haircoats of the genetically modified animals were not smooth. Unlike those of the normal mice, their coats were wavy. (That’s more or less the mouse version of uncombable hair.)

Betz says the study one day could lead to genetic tests to diagnose uncombable hair syndrome. If doctors could confirm a child inherited the mutant gene, this could help parents who are concerned.

Drug companies might even use the new data to devise treatments. But Betz thinks they won’t be interested just yet. Because the condition is so rare, there wouldn’t be many customers.

As a dermatologist, Shani Francis is an Illinois doctor who treats people with skin and hair diseases. She also teaches at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Medicine. The new study provides “exciting new information,” she says, because no one had identified genes linked to uncombable hair syndrome before. Plus, the study may help scientists understand other abnormalities affecting hair’s structure. These include the common problem of split ends, when the end of hair strands split into two parts. The findings could even help researchers tackle a problem in which bumps appear along hair strands — a condition known as bamboo hair.