Super Sticky Power

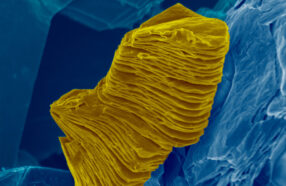

Scientists have combined the sticking power of geckos and mussels to create an extrasticky material.

By taking advantage of the natural abilities of geckos and mussels to stick to various surfaces, scientists have created a material far stickier than glue.

H. Lee, W. Lim, and A. Kane; adapted by L. Steenblik Hwang