Will we know alien life when we see it?

Recognizing life on other worlds requires wiggle room in the definition of ‘life’

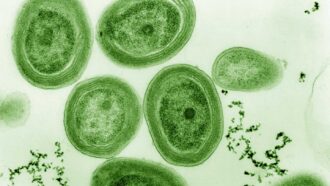

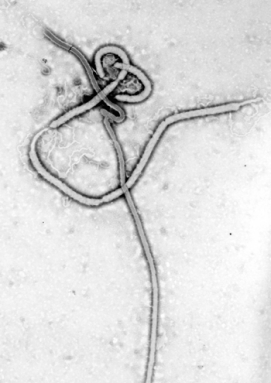

Movies have suggested that any alien species from other planets or faraway moons are likely to look like this. Scientists, however, suspect that we are more likely to encounter one-celled species able to survive harsh environments.

cosmin4000, homeworks255, fergregory, den-belitsky/iStockphoto; composite by L. Steenblik Hwang

This is the third in a three-part series on the search for extraterrestrial life.

In a 1967 episode of Star Trek, Captain Kirk and his crew investigated the mysterious murders of miners on the planet Janus VI. The killer, it turned out, was a rock monster called the Horta. But the Enterprise’s sensors hadn’t registered any sign of life in the creature. The Horta was a silicon-based life-form. That made it different from any on Earth where everything is carbon-based.

Still, it didn’t take long to determine that the Horta was alive. The first clue was that it skittered about. Spock closed the case with a mind meld. He learned that the creature was the last of its kind, protecting a throng of eggs.

But recognizing life on different worlds isn’t likely to be this simple. It could prove especially hard if the recipe for life elsewhere does not include familiar ingredients. There may even be things alive on Earth that have been overlooked because they don’t fit standard definitions, some scientists suspect. The scientists that look for life outside Earth are called astrobiologists. They need some ground rules — with some built-in wiggle room — to know when they can confidently declare, “It’s alive!”

Among people working out those rules is Christoph Adami. He is a theoretical physicist at Michigan State University in East Lansing. He has watched his own version of silicon-based life grow. That life wasn’t real, though. It was a computer simulation.

“It’s easy when it’s easy,” Adami says. “If you find something walking around and waving at you, it won’t be that hard to figure out that you’ve found life.” But chances are, the first aliens that humans encounter won’t be little green men. They will probably be tiny microbes of one color or another — or perhaps no color at all.

Story continues below video

By definition

Scientists are trying to figure out how they might recognize those alien microbes. It could be really hard if the microbes are very strange. This has led researchers to propose some basic criteria for distinguishing living from nonliving things.

Many insist that certain features must be present for any type of life, including aliens. These include an active metabolism, reproduction and evolution. Others add the requirement that life must have cells big enough to contain protein-building machines called ribosomes (RY-boh-soams).

But such definitions can be overly strict. Making a list of needed criteria for life may give scientists tunnel vision, says Carol Cleland at the University of Colorado Boulder. That narrow vision could blind them to the diversity of life across the cosmos.

Some scientists, for instance, say viruses aren’t alive because they rely on their host cells to reproduce. But Adami has “no doubt” that viruses live. “They don’t carry with them everything they need to survive,” he acknowledges. “But neither do we.” What’s important, Adami argues, is that viruses transmit genetic information from one generation to another. And at its simplest, he contends, life is just information that reproduces itself.

Evolution should be off the table, too, Cleland says. After all, people would likely never be around long enough to tell whether something is evolving.

Even restrictions on cell sizes may squeeze the tiniest microbes out of consideration as aliens. Yet it shouldn’t, argues Steven Benner. He’s an astrobiologist at the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in Alachua, Fla. A cell too tiny to contain ribosomes may operate another way. Instead of proteins, it might use genetic material known as RNA to carry out biochemical reactions, he speculates.

Cells have been thought necessary because they separate one organism from another. But layers of clay could do that, Adami suggests. Cleland proposes that life might even exist as networks of chemical reactions — ones that don’t require any separation at all.

It’s fantastical thinking. But that may just be what it takes for scientists to recognize unusual types of life, should such aliens turn up.

Up close and personal

In recent years, more than 1,000 planets have been spotted outside our solar system. With their discovery, the odds favoring the existence of alien life are better than ever. But even the most powerful telescopes can’t image distant life, especially if its microscopic. Chances of finding such tiny life improves if scientists can reach out and touch it.

And that means looking within our solar system, says Robert Hazen. He’s a a scientist who studies minerals, working at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C.

“You really need a rover down on its hands and knees analyzing chemicals,” he says. Such rovers are now sampling rocks on Mars. The Cassini space probe has bathed in the geysers spewing from Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus. Such robot explorers may one day send back signs of life. But only subtle signs of life — what scientists call “biomarkers.” And it may be very hard to tell true biomarkers apart from just some mineral, he notes, especially at a distance.

“We really need to have life be as obvious as possible,” says Victoria Meadows. By obvious, she partly means Earth-like. She also partly means that this signal must be one that no chemical or geologic process alone could have left behind. Meadows is an astrobiologist with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. She heads its Virtual Planetary Laboratory at the University of Washington in Seattle.

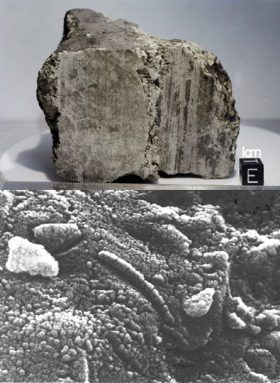

Some scientists say life is an “I’ll know it when I see it” phenomenon, says Kathie Thomas-Keprta. But life also may be in the eye of the beholder. Thomas-Keprta knows this all too well from studying a Martian meteorite. She is a planetary geologist. She was part of a team at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston that studied a meteorite named ALH84001. (It was discovered in Antarctica’s Allan Hills ice field in 1984.)

The team was led by Thomas-Keprta’s late colleague David McKay. In 1996, the scientists claimed that carbonate globules embedded in the meteorite looked a bit like microscopic life on Earth. The researchers found large organic (carbon-based) molecules. That indicated they formed at the same time. Thomas-Keprta also identified tiny crystals of magnetite overlapping the globules. These iron-based crystals looked much like ones made by certain bacteria on Earth. Such bacteria use chains of the crystals as a compass as they swim in search of nutrients.

In the end, the scientists concluded they were looking at fossils of ancient Martians.

Other scientists disagreed. The globules and crystals might have formed through other processes, critics said — with no life needed.

That initial claim of fossil Martians has now been widely dismissed.

But you may not need to leave our planet to find aliens. There’s the possibility of shadow life on Earth. It could be so strange that it has so far gone unrecognized, posits Cleland at the University of Colorado. Consider, she says, “desert varnish.”

These are the dark stains on the sunny sides of some rocks in super-dry climates. Some scientists think certain bacteria or fungi might be responsible. Odd, communal microbes could be sucking energy out of the rocks. They might use this energy to fuel their creation of that hard outer coat of minerals. Such organisms might produce the varnish by cementing iron and manganese to clay and silicate particles.

Curious, some scientists have tried to re-create desert varnish in the lab. They used fungi and bacteria. And they failed.

In the wild, those varnishes form over millennia. Critics have argued that this is too slow to be something created by microbes. But how do we know, Cleland asks? “We have an assumption that life on Earth has a pace,” she says. Some shadow life may instead grow far more leisurely.

Mineral distortions

To find life, and classify it correctly, look for the odd thing out, suggests Hazen. He is looking for messages in minerals. Minerals do not occur evenly across the landscape. There are 4,933 recognized minerals on the planet, Hazen says. He and his crew have mapped the locations of 4,831 of them. And 22 percent of these exist in only one site. Close to 12 percent more occur in just two places.

One reason for this skewed distribution is that as life has evolved, it has used local resources, turning them into new minerals. Take for example hazenite. (Yes, it’s named for Hazen.) This phosphate-based mineral is found only in California’s Mono Lake. Microbes living there are its only source. Other species may have led to similarly rare pockets of some mineral, Hazen’s group suspects.

Finding such odd distributions of minerals on other planets or moons might indicate that life exists there, or once did. Hazen has advised NASA on how rovers might identify such mineral clues to life on Mars.

Mars was once wet. It still has occasional running water. That shows it may once have been capable of hosting life. This and other evidence in 2013 led Benner, of the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution, to suggest that Mars may have seeded the life now on Earth. Whether that idea holds up may depend on finding Martians.

But Benner doesn’t seem worried. “I would be surprised now if they don’t find life on Mars,” he says.

Missions could easily bring astronauts to Mars to confirm a suspected find, says Dirk Schulze-Makuch. He’s an astrobiologist at Washington State University in Pullman. “If someone with a microscope sees a microbe and it “is wiggling and waving back, that’s really hard to refute,” he jokes.

Going for the less obvious

But humans and even probes may have a harder time spotting life on more distant or exotic locales. Prime targets are the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. E.T. hunters are attracted to Europa and Enceladus because their liquid oceans slosh beneath icy crusts.

Liquid water is thought to be necessary for many of the chemical reactions that could support life. But water is actually a terrible solvent for building complex molecules on which life could be based, Schulze-Makuch notes. Instead, he thinks really alien aliens might have spawned at hot spots deep in the hydrocarbon lakes of Titan, Saturn’s biggest moon. “Whether you can get all the way to life, we don’t know,” he says.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for Titanic life is the extreme cold, says Paulette Clancy. She’s a chemical engineer at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. This moon is so frosty that its methane — a gas on balmy Earth — is a viscous, almost-frozen liquid. And water, she says, “would be like a rock.” Under those conditions, she notes, organisms with Earth-like chemistry wouldn’t stand a chance. For one thing, the membranes that hold in an Earth cell’s guts wouldn’t work on Titan.

But Clancy and her colleagues simulated experiments under Titan-like conditions. And certain short-tailed molecules could spontaneously create stable bubbles, they found. Those bubbles are similar to cell membranes.

Like desert varnish, life on Titan may grow slowly. There is little sunlight or heat. Its frigid temperatures would keep chemical reactions sluggish. So if life were to exist here, Schulze-Makuch imagines it would have lifespans perhaps millions of years long. Organisms might reproduce — or even breathe — just once every thousand years!

With so many options out there, Clancy predicts that there are several planets or moons with life on them. Many other researchers are also optimistic that life is out there to find. In the future, astrobiologists may come face-to-face with E.T. And when they do, they might even recognize it for what it is.