Is your home chilly? This might just be healthy

Exposure to mildly cold temperatures can help fight obesity and diabetes

Feeling cool — literally — forces the body to fire up its internal furnace. That burns fuel, or calories, which can help people shed unwanted weight.

Max Pixel (CC0)

Getting a bit chilly or overly warm may not be comfortable, but it can be healthy, research now suggests. And that’s especially true for people who carry too much body fat or who suffer from type 2 diabetes.

These temperature benefits have to do with our metabolism — the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions at work inside cells. The faster someone’s metabolism, the more calories a body will burn. Burn more calories than you ate and you will shed some pounds.

Being mildly cold speeds up your metabolism. In other words, it forces the body’s furnace to stoke up. It does this to help the body maintain a healthy temperature of around 37° Celsius (98.6° Fahrenheit).

In people with type 2 diabetes, exposure to mild cold also improves the way their bodies respond to sugar. Unless their disease is controlled, it can boost the risk of heart disease, coma — even death.

Wouter van Marken Lichtenbelt is a biologist in the Netherlands at Maastricht University. He studies how environmental factors, such as temperatures, influence human health. Mild cold and heat can help manage both obesity and diabetes, he says. He came to this conclusion after poring over data from a range of studies that he and others have done. His team detailed its reasoning in a paper published April 26 in Building Research & Information.

As a review paper, its authors sifted through a host of published data by research teams across the world to see if any useful trends emerged. In some cases, these trends may not have shown up in individual papers, but only by looking at a host of related ones on a particular topic.

Most research about temperature’s effect on the human body has focused on extremes of hot and cold. Van Marken Lichtenbelt instead homed in on impacts of milder variations in temps experienced in everyday life. Such findings are important, he argues, because people spend a lot of time indoors. Most buildings and homes are set to a constant and comfortable temperature, around 21 to 22 °C (69.8 to 71.6 °F).

But the patterns his team extracted from looking at lots of research now suggest that “we should not assume comfortable is always healthy,” he says. “Sometimes you have to get out of your comfort zone.”

Sifting through the data . . .

One study that contributed to this conclusion was published in 2013 by van Marken Lichtenbelt’s group. It had exposed 17 healthy people in their early 20s to mild cold. Over the course of 10 days, these recruits spent an increasing number of hours in a temperature-controlled room. Its thermostat was set at 15 °C (59 °F).

The volunteers had to spend two hours in the room on the first day and four hours on the next. Every day after that, everyone stayed in that chilly room for six hours.

“Most subjects were slightly shivering at the start, but less so at day 10,” recalls van Marken Lichtenbelt. More importantly, by day 10, their metabolisms had sped up. These people burned about 30 percent more calories, on average, than they had before the experiment had begun.

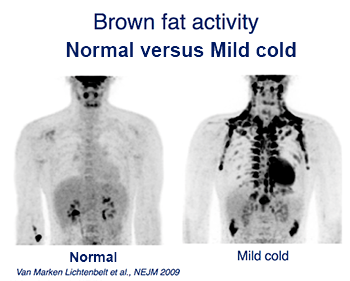

That energy to keep the body temperature uniform came largely from the body’s store of brown fat, van Marken Lichtenbelt showed. Normal body fat is white. As brown fat’s name suggests, this type looks a bit dark. More importantly, it functions differently than white fat.

White fat is what the body makes from excess fuel (food) for which the body has no immediate need. This white fat can be burned as energy. But mainly it just sits around like a kitchen pantry, becoming a storehouse. The body only turns to it as a reprieve from extreme hunger — what you’d think of as starvation.

Brown fat, in contrast, doesn’t convert its stored fuel into heat when someone is starving. Cold temperatures activate it. Regular exposure to mild cold seems to kick start the body’s burning of brown fat. And this is true whether someone is fat or lean. However, brown fat tends to be less active in obese people. So reigniting it with cold temps might be a strategy to help those who are overweight slim down.

There is less research on the effects of mild heat. The few studies that exist suggest its effect on the body is not as dramatic as chilly temps, says van Marken Lichtenbelt. Any boost seen in metabolism probably reflects the fact that the heart speeds up when the body gets too warm.

Chilly temps: Therapeutic for diabetics?

In 2015, van Marken Lichtenbelt’s team asked people with type 2 diabetes to endure the same chilly conditions as the healthy participants had in the earlier study. All eight people were in their 50s or 60s (an age at which type 2 diabetes tends to emerge). And cool indoor temps showed signs of helping them.

Type 2 disease is characterized by the body’s inability to manage sugar properly. Normally insulin shepherds that sugar into cells where it can fuel their activities. But in this disease, the body begins resisting — partially ignoring — that hormone. When this happens, high levels of glucose (a type of sugar) will accumulate in the blood. And that’s bad for blood vessels and more.

After 10 days of exposure to the mildly cold indoor temps, the scientists tested their participants’ blood. It showed that their insulin now worked 40 percent better than it had before the study began. That means their bodies were better able to process sugar. The researchers aren’t exactly sure why this happened. They do, however, suspect it too had something to do with activating the body’s brown fat.

In any case, the 40 percent improvement in insulin sensitivity is significant. It’s similar to what van Marken Lichtenbelt and his colleagues saw in another study of diabetic patients who were taking medicine and exercising.

What should people make of all this?

Studies such as these show that it’s important to move between different temperature zones, concludes Susan Roaf. She is an architect in Scotland who specializes in adapting buildings to different climates. Roaf works at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh and was not involved with these studies.

Moving between different indoor temperatures helps to make sure our body’s system for regulating temperature — including its burning of brown fat — stays healthy, she says.

“Respect your deep core temperature and the systems that keep it stable,” Roaf recommends.

A good place to start is at home or work, van Marken Lichtenbelt says. Turn the temperature down or up. “Indoor air temperatures are not going to save the world,” he says. However, he adds, this “is one lifestyle factor that could improve our health.”