Drug-detection system could help partygoers protect themselves

Worn as a bracelet, it allows people to test their alcoholic drinks for the presence of hidden drugs

Parties can be fun. But where alcohol is served, there can also be some unexpected danger: drugged drinks. One teen invented a way to alert her friends to the risk.

shironosov/istockphoto

Content warning: This post contains references to sexual assault.

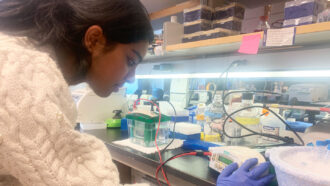

Pittsburgh, Pa. — In Brazil, partying on the beach can be dangerous for girls. Guys can slip a drug into someone’s drink. That drug can cause the drinker to pass out, leaving her vulnerable to sexual assault. “It’s very common, I’ve seen friends go through it,” says Isabela Dadda dos Reis, 17. “It really bothered me.” Fed up, she developed a low-cost bracelet that would allow partiers to test their drinks — and alert them if that drink has been tampered with.

A color-change chemical identifies the presence of the drug. It also offers a rough estimate of how much drug is present. “You can see the color change with the naked eye,” Isabela notes. That makes it useful in the real world, such as at a party.

Isabela is a senior in Osório, Brazil. She attends the Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Rio Grande do Sul (IFRS).

In Brazil, teens can legally drink at age 18. (In the United States, the legal drinking age is 21.) And there have been many cases in which people drug drinks using chemicals called benzodiazepines (BEN-zoh-dy-AZ-eh-peens). Doctors normally prescribe such drugs to reduce symptoms of anxiety.

Taking these drugs to treat anxiety is fine. However, Isabela explains, “When combined with alcohol, they have a terrible effect.” They can cause someone to faint. The person who has been drugged may not remember what happened when they wake up the next day. This unwanted side-effect is well known. That explains why labels on these prescription drugs warn against their use in the presence of alcohol.

Criminals have been known to use these drugs to commit sexual assault. In Brazil, a drink that has been spiked with one of these drugs is called “good night, Cinderella.” Isabel notes that many sexual assault crimes reported in Brazil happen with benzodiazepine drugs.

These drugs are hard to detect. They don’t have a tell-tale taste. They also leave the body quickly. The next morning, if someone can’t remember things or feels bad, people might just blame the drinks and not the drugs. “You could say the person has a hangover and anyone would believe it,” Isabela says.

She wanted some way to find out if a drink had been drugged before someone drank it. Key to her success was identifying a chemical that changed color when a benzodiazepine was present.

Validating her success

Isabela tested her color-changing chemical against different concentrations of three drugs: alprazolam, clonazepam and diazepam. Alprazolam is the active ingredient in Xanax. Clonazepam is the muscle relaxant sold as as Klonipin. Diazepam is the anti-anxiety drug commonly sold as Valium. She is not identifying her chemical, she says, because she plans to patent its use for these drug-detection bracelets.

To test how well the system works, she ground up half a pill, one pill and two pills of each drug. Then she added those amounts to vodka, whisky and an orange liqueur. All are popular drinks in her town. Each drink changed color when one of the drugs was present. If the drink is clear, the chemical reacts with the benzodiazepine in it to turn the drink pink. If the beverage is dark, the chemical makes it much, much darker.

She measured that color change using a spectrophotometer (SPEK-troh-foh-TOM-eh-tur). This instrument can measure how much light is passing through something — such as a drop of whisky.

No one has access to such a device at a party. So Isabela developed a bracelet that could perform some of the same functions. It’s got a small plastic cup on top, with a light underneath. The cup is divided in half. All a partier has to do is put Isabela’s compound in one side and pour the drink in both sides. If the drink changes color on the side with the compound, the drink may have been drugged. “You’re not putting the chemical reagent into the whole drink,” she explains. “If it’s clear, you can still drink it.”

The teen showcased her drug-detecting jewelry here, this week, at the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). Created by Society for Science & the Public, this competition brings together almost 1,800 high school students from 81 countries to present their winning science-fair projects. This year, ISEF is sponsored by Intel. (Society for Science & the Public also publishes Science News for Students and this blog.)

Isabela’s prototype bracelet system is washable. That means it can be used over and over for each new drink or party. The teen would like to get a patent to make and sell her bracelet for anyone who needs it. Right now, her prototype costs only $0.53 to make.

Someday, the teen hopes, parties will sell or give out her bracelet along with the I.D. bracelets people wear to show they are old enough to drink. That way, people can still party — and stay safe.

Update: At ISEF, Isabela’s work won a second place award of $3,000 from the American Chemical Society. She also won a third-place award in the Chemistry category, taking home another $1,000, and picked up an honorable mention from the American Statistical Association for her work.