Novel fabric could turn perspiration into power

Sweat already works to cool you down; this teen also wants it to power you up to get even cooler

People sweat to stay cool. But one teen wants to punch up the power of perspiration.

wundervisuals/E+/Getty Images Plus

PHOENIZ, Ariz. — When sweat is dripping down your face (or armpits), you might think it’s just a sign of hard work. But as sweat dries, it removes some heat with it, cooling you down. A young researcher now wants to empower sweat to do even more. He wants it to help athletic wear further cool the bodies of hard-working athletes. Its name? The sweatshirt, of course.

Rohit Nemani, 17, has been on the Cox Mill High School varsity cross-country team for three years. Running in the hot, sticky summers of Concord, N.C., will make anyone aware of just how much the human body can perspire. Sweat cools the skin, of course. But sometimes it’s not enough. “Every year, tons of athletes put themselves at risk from overheating, dehydration and heatstroke from working out in hot climates,” Rohit says.

One day while running (of course), the teen came up with an idea to use sweat itself to power an improved cooling system.

Sweat isn’t just water and smell. It has salts, too. Those salts are electrically charged particles that can produce electricity when they contact an electrode — a device that conducts electricity. If Rohit could weave electrodes into the fabric of a shirt, he reasoned, he could use those salts to generate electricity.

He’d then use that electricity to power an actively cooling fabric that he will put into the body of the sweatshirt. When it receives a little electric power, this fabric pulls sweat up from the skin and spreads it out. That increases the amount of water that evaporates to keep someone cool. Start sweating and that salty moisture powers the super-cooling fabric, Rohit says. “When it cools you down, you sweat less.” That, in turn, will turn off power to the fabric. Then, as someone sweats more again, the electricity returns and the cooling fabric goes back to work.

Building a better sweatshirt

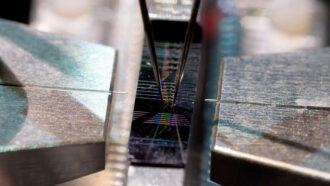

The first trick to creating his better sweatshirt was figuring out how to weave materials such as carbon and zinc into a shirt. They would transfer any of the electricity created by the sweat. It turns out that this isn’t easy. So Rohit emailed universities near him in search of a scientist who would let him have access to special 3-D printers. He finally heard back from Jesse Jur at North Carolina State University in Raleigh. Jur let the student use his equipment to print carbon and to attach zinc washers onto his fabric — allowing the fabric to conduct electricity.

Now Rohit has fabric that can make electricity from sweat. The inner cotton layer soaks up this moisture from the skin by what’s known as capillary action. The next layer is polyester. Being hydrophobic (Hy-droh-FOH-bik) — it repels water. That spreads the sweat out, allowing it to come into contact with the carbon and zinc electrodes. Salts in the sweat react with the carbon and zinc pressed into the shirt, producing tiny amounts of electricity.

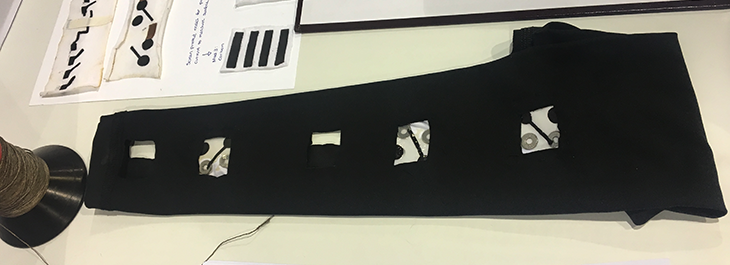

By pouring artificial sweat (salt and water) onto a prototype shirt sleeve, Rohit found that half a milliliter of sweat (a tenth of a teaspoon) can produce about 0.6 to 0.7 volt of electricity.

By linking electrodes in this sleeve together with metallic yarn — strands that can conduct electricity — those partial volts added up. Right now, Rohit gets about 1.7 volts off his sleeve. It’s just enough to power the actively cooling fabric.

Rohit brought a sample of his new sweatshirt system here to the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. This competition was created by Society for Science & the Public in 1950 and is still run by this organization. (The Society also publishes Science News for Students.) This year’s fair was sponsored by Intel. It brought together more 1,800 students from 80 countries to share their award-winning science fair projects.

To date, Rohit has built only the one sleeve. Eventually, he hopes to weave together the electricity-conducting sleeve and active-cooling fabric into a full, prototype shirt. He has already changed the fabric’s design to make it flexible and stretchy — ideal for athletic wear. To keep the shirt lightweight, he also wants to reduce how much carbon and zinc it uses to produce electricity. And don’t worry, the shirt is already washable.

The teen can think of lots of people who might want such a super-cool sweatshirt. “There’s obviously athletes trying to increase their performance,” he notes. He also points to “people in the military and anyone who works outside in [hot] conditions” that could put them at risk of heatstroke. Rohit hopes his shirt can help them by squeezing just a little more cooling out of every drop of sweat.