Prehistoric air travel

Flying reptiles might have crossed oceans, continents nonstop

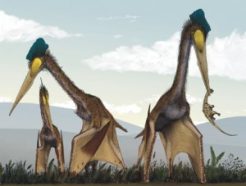

But for a certain flying reptile that lived 70 million years ago, 10,000 miles probably wasn’t too far to fly in one trip, according to Michael Habib. In a recent study, Habib described four giant types of these beasts, called pterosaurs, which might have been able to go the distance in a single flight. (Pterosaurs were not dinosaurs but were closely related to dinosaurs and lived at the same time as some dinosaurs.)

If his calculations are correct, then the giant pterosaurs are “the longest single-trip-distance fliers in the Earth’s history,” Habib told Science News.

Habib is a scientist at Chatham University in Pittsburgh and researches biomechanics. Biomechanists use physical laws about motions and forces to study how bodies work. In this case, Habib used the estimations and measurements of the size and anatomy of pterosaurs that other scientists had made, and calculated how far the creatures could fly without resting.

Scientists who study fossils say these beasts stood as tall as giraffes and flew through the air on 30-foot-long wings. Some researchers have also estimated that the biggest type of these creatures weighed about 550 pounds, which is more than an ostrich. (Other researchers suggest this estimate is too high.)

In other words, if you take a time machine back at least 65 million years and want to see a pterosaur, you probably won’t have much trouble. Just look for the nearest giant, flying reptile with a wingspan as wide as a backyard swimming pool.

It’s no small feat to haul that much weight 10,000 miles through the air. The animals had to use their wings efficiently. Habib assumed the pterosaurs flew by some combination of flapping and gliding — probably gliding between flapping sessions. They might also have been able to hitch a ride on thermals — air currents that rise from warmed patches of earth — and other currents in the atmosphere.

If Habib is right, then a pterosaur could have crossed a continent or ocean in a single flight. That means that pterosaur fossil remains found on different continents may not come from different species. Different animals of the same species may have been able to travel all over the world.

“A pterosaur from Big Bend [Texas] could be mating with a pterosaur from Transylvania,” Habib said during a recent meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, when he presented this work to other scientists.

Habib’s work rests on a lot of assumptions. He had to make “best-guess” estimates for the mass, shape and abilities of the pterosaur — and he applied methods from other studies to understand how the animals might have flown. Other scientists may disagree with these estimates and the conclusions Habib draws from them — and still others will do their own studies.

But that’s par for the course in science, and as a result, our understanding of pterosaurs will improve. It’s not as though we’ll ever know exactly how pterosaurs behaved — since they haven’t been around for awhile.