Ozone hits a new low

Scientists discover a major thinning in the protective atmosphere over Arctic

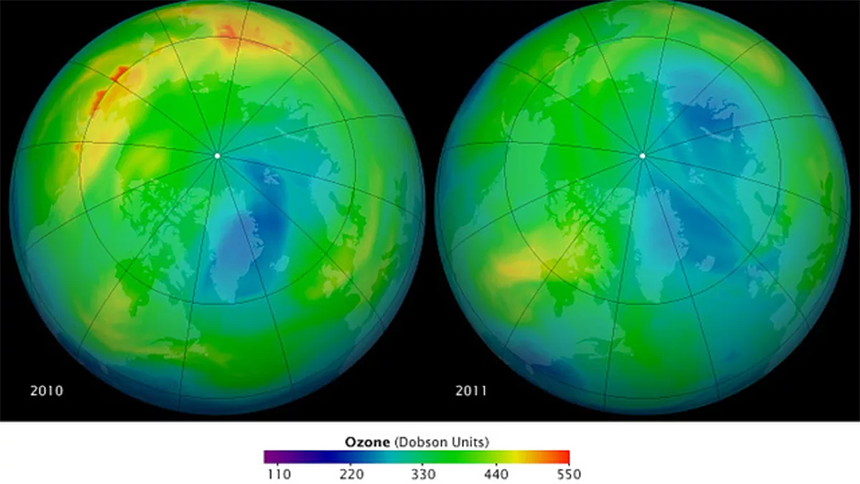

On the right is a view of the North Pole in the spring of 2011. At left is the same view, in 2010. Blue areas show low levels of ozone in the stratosphere.

NASA

Scientists saw something missing in the skies over the North Pole this spring. And it wasn’t Santa or his reindeer. It was ozone — an invisible gas that protects Earth and everything on it from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays.

The thickest layer of ozone is found high up in the stratosphere. The thickness of the ozone layer changes throughout the year. Sometimes there’s more; sometimes there’s less. Scientists say that in the spring of 2011, there was less ozone high above the Arctic than ever before. The envelope had grown thin.

The scientists who measured the loss called their discovery an “Arctic ozone hole.” Not all scientists like calling it a hole, because some amount of ozone remained. No matter how people describe it, the ozone layer was way low. And less ozone means that more harmful UV rays were able to reach Earth’s surface.

“It was significantly worse than anything we have ever seen,” Geir Braathen told Science News. Braathen is an atmospheric chemist who works at the World Meteorological Organization in Geneva, Switzerland. (Atmospheric chemists study the molecules and chemical reactions that happen in the sky.) Braathen knows about the new study but did not work on it.

Usually, news about the ozone layer focuses on the sky over the southern hemisphere. Every year, a hole in the ozone layer opens up over Antarctica. Braathen told Science News that every spring, 70 percent of the ozone above the icy continent goes away, and in some high swatches of the Antarctic’s stratosphere there’s no ozone at all.

Ozone over northern regions doesn’t decrease as much as ozone over Antarctica. In the new study, however, the scientists say that in 2011, the Arctic drop in ozone started to look similar to Antarctica’s.

“The magnitude of the [Arctic] loss is comparable to that in the early Antarctic ozone holes in the mid-1980s,” Michelle Santee told Science News. Santee, who took part in the new study, is an atmospheric scientist. She works at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif. Right now, Santee says, ozone thinning in the northern stratosphere is nowhere near as bad as those in the south.

Scientists have learned the recipe for how to make ozone disappear from the atmosphere: Combine sunlight, a long period of cold temperatures and swirling winds that surround a patch of the stratosphere and keep fresh ozone out. Then add special clouds that help other molecules gobble up ozone. This year, all four of those ingredients came together over the Arctic, notes Nathaniel Livesey of JPL. Like Santee, he worked on the new study.

It might have been a random coincidence. On the other hand, some scientists worry that the situation will get worse as Earth’s surface warms. There’s no reason to suspect it won’t get worse, Ross Salawitch told Science News. Salawitch is an atmospheric scientist at the University of Maryland in College Park.

“I consider this to be a ‘big deal,’” he said.