Choked by bacteria, some starfish are turning to goo

Microbes that thrive in warm, nutrient-rich water are stealing the sea stars’ oxygen

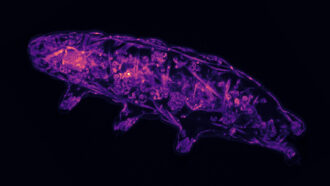

Starfish can develop wasting disease, such as this leather star (Dermasterias imbricata) did, seen at the Sitka Sound Science Center in Alaska. Affected sea stars can dissolve into a puddle of goo.

Ian Hewson

A mysterious culprit has been killing off starfish. Scientists had thought an infection was to blame. A new study does point to bacteria as the culprit. But the microbes appear to be suffocating those sea stars, not infecting them.

Many types of bacteria live close to the outer layers of a sea star’s skin. Some types can use up a lot of the water’s oxygen. Such microbes thrive in warm water where there are high levels of carbon-rich materials, called organic matter. When there are too many bacterial cells, they use up so much oxygen that they suffocate the starfish. Affected sea stars at such sites may just melt into a puddle of slime. Researchers reported these gooey findings January 6 in Frontiers in Microbiology.

The disease is known as sea-star wasting. Its symptoms include decaying tissues and loss of limbs. This disease first grabbed headlines in 2013. That’s when sea stars living off the U.S. Pacific Coast died in massive numbers. Outbreaks had occurred earlier, but never on such a large scale.

At first, scientists suspected a virus or bacterium might be making sea stars sick. A 2014 study did find a virus in unhealthy animals. But later studies found no link between the virus and sea-star deaths. That puzzled researchers.

The new study shows that a bloom of nutrient-loving bacteria can drain oxygen from the water, leading to sea-star wasting.

This finding “challenges us to think that there might not always be a single pathogen or a smoking gun,” says Melissa Pespeni. A biologist at the University of Vermont in Burlington, she was not involved in the work. It appears, she says, that the environment plays a big role in killing sea stars. And that, she says, “is a new kind of idea for [disease] transmission.”

The wasting disease is complex. That made it hard to figure out what was going on, says Ian Hewson. He led the research team. He’s also a marine biologist at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. His group’s hunt for why sea stars along North America’s Pacific Coast were melting into goo led them down many wrong paths. First, they thought the virus they found in sick sea stars in 2014 was to blame. But a year later, they disproved that idea. He and his colleagues then explored other factors, such as differences in water temperature. They also tried exposing the animals to bacteria. But nothing reliably triggered the wasting disease.

Then the researchers examined bacteria living with healthy starfish. They compared these microbes with those living along with animals that had the wasting disease. And, Hewson recalls, “That was when we had our ‘Aha’ moment.”

Suffocating starfish

His group noted higher levels of certain types of bacteria around starfish that started showing signs of injury. Some bacteria were copiotrophs (KOH-pee-oh-troafs). They’re microbes that thrive in areas with lots of nutrients. Also thriving were bacterial species that survive only in environments with little to no oxygen. To mimic these conditions in the lab, the researchers added nutrients to spur bacterial growth in the tubs in which the animals were living. Sure enough, the sea stars began wasting.

Hewson’s team also tried lowering oxygen levels in the water. That had a similar effect. It caused wounds in three out of every four animals. In contrast, no sea star getting normal oxygen levels got sick.

Starfish breathe as oxygen diffuses over small external projections called skin gills. Growing copiotrophs suck lots of oxygen out of the water. That may leave sea stars struggling to breathe. It isn’t yet clear why low oxygen triggers a wasting. Many of the animal’s cells may simply die.

Not contagious, but a ‘snowball effect’

The disease isn’t caused by a contagious pathogen. Still, the wasting spreads. Dying sea stars generate more organic matter. And that may spur bacteria to grow on nearby healthy animals. “It’s a bit of a snowball effect,” Hewson says.

His team also analyzed tissues from starfish that had succumbed in a mass die-off between 2013 and 2014. It followed a large algal bloom on the U.S. West Coast. The researchers wanted to see if conditions similar those in an algal bloom might explain that outbreak. The dead sea stars’ tissues had high amounts of a form of nitrogen found in low-oxygen conditions. That’s a sign that those starfish might have died from a lack of oxygen, too.

The problem may worsen with climate change, Hewson worries. Based on physics alone, he notes, “warmer waters can’t [hold] as much oxygen [as colder water can].” Bacteria such as copiotrophs also flourish in warm water.

Pinpointing the likely cause of wasting could help experts better treat sick starfish, Hewson says, at least in the lab. It might be possible to boost oxygen levels in a water tank to make this gas more available to sea stars. Or researchers could get rid of extra organic matter with ultraviolet light or water filters.

“There’s still a lot to figure out with this disease,” Pespeni says. “But I think [this new study] gets us a long way to understanding how it comes about.”