Americans consume some 70,000 microplastic particles a year

Estimating how much plastic we eat, drink and breathe will help determine health risks

Bottled water can be a source of microplastics.

AntionioGuillem/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Bits of plastic too small to see are in the air we breathe. They are in the water we drink and the food we eat. How many of them do we consume? And how does they affect our health? A team of researchers has now calculated an answer to the first question. Answering the second, they say, will require more study.

The team estimated that the average American consumes more than 70,000 particles of microplastics per year. People who drink only bottled water could consume even more. They could be drinking in an additional 90,000 microplastic particles per year. That’s probably from microplastics leaching into the water from the plastic bottles. Sticking to tap water adds only 4,000 particles annually.

The findings were published June 18 in Environmental Science & Technology.

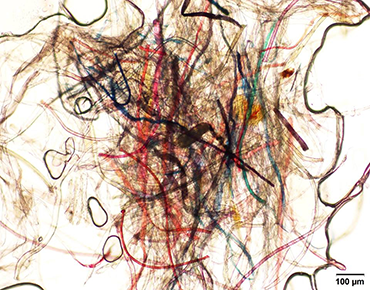

Scientists have found microplastics all over the world — even in mosquitoes’ bellies. These tiny bits of plastic come from many sources. Some are created after plastic waste in landfills and oceans breaks down. In water, plastic breaks down when it’s exposed to light and wave action. Clothes made of nylon and other types of plastic also shed bits of lint as they are washed. When wash water goes down the drain, it can carry that lint into rivers and the ocean. There, fish and other aquatic creatures will eat it.

The scientists behind the new study hope that by estimating how much plastic people eat, drink and breathe, other researchers can figure out the health effects.

That’s because we need to know how much plastic is in our bodies before we can talk about its effect, explains Kieran Cox. Cox is a marine biologist who led the study. He’s a graduate student in Canada at the University of Victoria. That’s in British Columbia.

“We know how much plastic we’re putting into the environment,” says Cox. “We wanted to know how much plastic the environment is putting into us.”

Plastics abound

To answer that question, Cox and his team looked at previous research that had analyzed the amount of microplastic particles in different items that people consume. The team checked fish, shellfish, sugars, salts, alcohol, tap and bottled water, and air. (There wasn’t enough information on other foods to include them in this study.) This represents about 15 percent of what people typically consume.

The researchers then estimated how much of these items — and any microplastic particles in them — that men, women and children eat. They used the U.S. government’s 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans to make their estimates.

Depending on a person’s age and sex, Americans consume from 74,000 to 121,000 particles per year, they calculated. Boys consumed just over 81,000 particles per year. Girls consumed a little less — a bit more than 74,000. This was probably because girls typically eat less than boys. These calculations assume that boys and girls drink a mix of bottled and tap water.

Because the researchers considered only 15 percent of Americans’ caloric intake, these could be “drastic underestimates,” says Cox.

Cox was especially surprised to learn there are lot of microplastic particles in the air. Until, that is, he thought about how much plastic we are surrounded by every day. As that plastic breaks down, it can get into the air we breathe.

“You are probably sitting around two dozen plastic items right now,” he says. “I can count 50 in my office. And plastic can settle out of the air onto food sources.”

Risk factors

Scientists don’t yet know if or how microplastics could be harmful. But they have reason to worry. Plastics are made from many different chemicals. Researchers don’t know how many of these ingredients might affect human health. However, they do know that some ingredients can cause cancer. Polyvinyl chloride is one of those. Phthalates (THAAL-ayts) are also dangerous. These chemicals, used to soften some plastics or as solvents, are endocrine disruptors. Such chemicals mimic hormones found in the body. Hormones trigger natural changes in cells’ growth and development. But these chemicals can fake out the body’s normal signals and lead to disease.

Plastic alsocan act like a sponge, soaking up pollution. The pesticide DDT is one type of pollution that’s been found in plastics floating in the ocean. Polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, are a second type.

We don’t yet know enough to determine the risk of consuming microplastics, says Sam Athey. She studies sources of microplastics. She’s a graduate student in Canada at the University of Toronto in Ontario. “There are no guidelines or published studies on ‘safe’ limits of microplastics,” she notes.

Some researchers have shown that humans pee out microplastics, she says. But what’s not clear is how long microplastics take to move through the body after they’ve been consumed. If they stay in the body for just a short time, the risk of negative health effects might be lessened.

Some research suggests that breathing in microfibers (plastic and natural materials) might inflame the lungs, Athey says. This might increase the risk of lung cancer.

Erik Zettler agrees there isn’t enough research yet to responsibly estimate health risks. He’s a scientist who studies plastic marine debris. Zettler works at NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research in Den Berg.

But like Cox, Zettler sees this study as a first step in figuring out the risks. For now, he says, it’s a good idea to “minimize exposure where we can.” His advice: “Drink tap water, not bottled water, which is better for you and the planet.”

Cox says doing the study made him change some of his behaviors. When it was time to replace his toothbrush, for example, he bought one made of bamboo, not plastic.

“If you have the freedom to chose, make these small choices,” he says. “They add up.”