Here’s what puts teen drivers at greatest risk of a crash

Just-licensed teens are roughly four times as likely as adults are to crash their cars

Teen drivers are more likely to get into car crashes than adult drivers. Inexperience and a greater inattentiveness to what’s happening on the road play appear to foster those youthful accidents, data show.

bowdenimages/iStockphoto

Car wrecks are the leading cause of death for U.S. teens. In fact, adolescents are twice as likely as adults are to get into a wreck. The first 18 months after teens get their license are the most dangerous. During that time, new drivers are four times more likely than adults to get into an accident. The reason: inexperience and a tendency to get distracted, studies now show.

No matter how careful they are, all teen drivers start off inexperienced. And each will face many distractions. These can be anything from cell phones and chatty passengers to the latest song from their favorite artist blaring on the radio. Early on, new drivers may be careful to stay sharp and avoid those distractions. But the more comfortable teens get behind the wheel, the more likely they are to text or engage in other risky behaviors. Even having a friend along for the ride can up the risk of a crash.

Those crashes claimed the lives of 1,972 U.S. teens in 2015 alone. Car accidents injured another 99,000 more.

Scientists are trying to find out what’s behind this heavy toll. They start by watching drivers in action. Some look at where a driver’s eyes are focused. Others study a driver’s personality to figure out which people are most likely to take risks when they get behind the wheel.

What these researchers are learning could lead to new tips that keep young drivers safe.

Eyes on the app

Drivers take their eyes off the road every time they snack, use their cell phone or search for something in their car. That puts anyone in or near that vehicle in danger. Teens know they’re supposed to avoid distractions — yet don’t.

Scientists in the United States and Canada teamed up to study why. They were particularly interested in teens who had just gotten a license to drive.

Charlie Klauer heads the Teen Risk and Injury Prevention Group at Virginia Tech Transportation Institute in Blacksburg. Her team analyzed 2006 data from a study of 42 newly licensed teens. Engineers had outfitted each new driver’s car with an accelerometer, GPS and video cameras. These tools let the researchers collect data on speed, whether a car was in the center of its lane and how closely a driver followed other cars. Researchers could see how many passengers were riding along and whether they wore seat belts. They could even see what was happening inside and outside the car.

Over the 18 months they were monitored, these teens became less likely to crash or have near misses. Some teens improved their driving skills. But many, despite becoming more comfortable behind the wheel, did not become safer drivers. As their experience increased, these teens became more likely to speed or drive recklessly. They also were more likely to make phone calls or text while driving. Teens with risk-taking friends were most likely to engage in risky behaviors.

Texting and dialing a phone are particularly dangerous. Looking away from the road for even half a second can result in a crash, Klauer notes.

“The average text message takes 32 seconds to compose,” she points out. The person writing it looks up and down repeatedly during that time. For a total of 20 seconds, their attention will not be on driving. Someone driving 60 miles per hour travels the length of about five U.S. football fields during the 20 seconds they are looking down. That creates an extremely dangerous situation.

What’s more, new technology is changing how people drive. From 2006 to 2008, when these data were collected, people used flip phones, Klauer points out. Now, with smartphones, drivers spend less time talking and more time texting and browsing. She knows this because her team repeated their data collection from 2010 to 2014 and again from 2013 to 2015.

The researchers are still analyzing their newest data. But they’ve found that browsing the internet while driving, and using apps like Instagram and Snapchat, have become common. These apps make drivers look down, Klauer says — not just to tap out a few letters, but also to see pictures or read entire blocks of text. That means the drivers were not focusing their attention on controlling their 1,800-kilogram (4,000-pound) vehicles.

What’s more, teens make poor choices about when to look down. Klauer’s team recorded teens checking their phones while driving through intersections when the light had just turned green. That’s when they should have been most vigilant.

It’s not just texting

Texting or checking social media while driving may seem like an obvious no-no. Both activities take your eyes off the road. So talking on the phone or to a passenger must be safer, right? Not necessarily.

Some studies show that fewer crashes happen when people are talking than when they are texting. But talking to another person still distracts a driver from what’s happening on the road. Researchers at the University of Iowa in Iowa City wanted to know how big an impact it has.

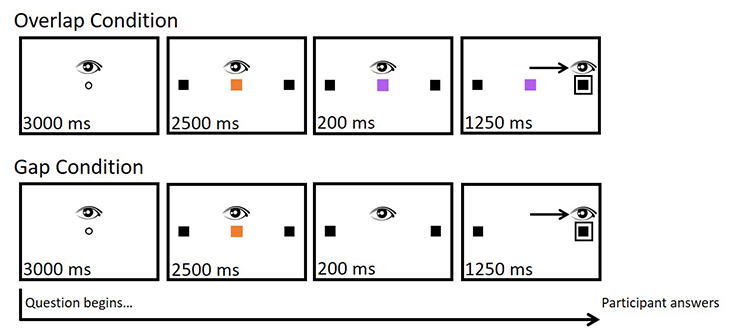

To find out, psychologists Shaun Vecera and Benjamin Lester performed two experiments. For one, they recruited 26 college students. All began each trial by staring at a colored square in the center of a computer monitor. After three seconds, a new square appeared to the left or right of the original. In some trials, called “gap” trials, the first square vanished before the second one appeared. In “overlapping” trials, the two squares overlapped for 200 milliseconds before the first one disappeared.

Before the testing began, the recruits were instructed to move their eyes to the new square as quickly as it appeared. Eye-tracking cameras recorded when and where the eyes looked throughout each trial.

But there was more to the trial than that. The students were asked a string of true-false questions as they completed some of the trials. Fourteen participants were told they didn’t have to respond to the questions. The rest were told they did.

And the second group actively listened to the questions, Vecera explains. He knows this because the students answered correctly more than 90 percent of the time. Clearly, they were paying close attention while doing the eye-movement task.

All participants were faster at moving their eyes in the gap trials — when the first square vanished before the second showed up. That’s because their attention had already been freed from the first square. Vecera calls this “disengagement.” When the two squares overlapped, participants had to break their attention from the first square before they could look at the second.

Participants were also faster when they could focus on the task without listening to any questions. Their eyes took longest to make the shift when they had to answer questions.

The second experiment was the same as the first, except that the questions were divided into ones that were “easy” and “hard.” Participants correctly answered 90 percent of the easy ones and 77 percent of the hard ones. Again, this shows that all had been paying attention to the questions.

How difficult a question was had no effect on slowing eye movements. Easy questions delayed eye movements just as long as the hard questions did. Just listening to and answering any kind of question took attention away from their other task — here, the need to shift where the eyes focused. Such movements are important because drivers need to constantly monitor their surroundings and adjust as needed.

“Disengagement takes around 50 milliseconds,” Vecera says. That’s the time it takes to shift your attention from the first square (or other object) to look at another. “But the time to disengage attention almost doubles when you are also actively listening to questions so that you can answer them,” his study found.

These findings are supported by a 2013 study. An MRI machine uses strong magnets to see which areas of the brain are active. A special type of this brain scanner, fMRI, highlights areas that become active as someone performs a particular activity — such as reading, counting or viewing videos. Researchers in Toronto, Canada used fMRI to record how brain activity changes during distracted driving. The machine had a steering wheel and foot pedals inside. The people being tested could, therefore, interact with the machine as though they were actually driving. Their “windshield” was a computer monitor with virtual roads and traffic.

The study tested 16 people. All were 20 to 30 years old. As their brains were scanned, the participants used the wheel and pedals to drive their virtual car. Sometimes they just drove. Other times, they were asked true-false questions while driving. The machine recorded their brain activity the entire time.

During normal (non-distracted) driving, areas near the back of the head were most active. These regions are associated with visual and spatial processing. But when the driver was distracted, those areas did less. Instead, an area behind the forehead — the prefrontal cortex — turned on. This part of the brain works on higher thought processes. When the participants were driving without distractions, that part of the brain had been doing little.

The evidence is clear: Talking while driving can be dangerous. “Having a cell phone conversation, even on a hands-free device,” says Vecera, reduces someone’s ability to shift their attention. That means a chatty driver may not respond quickly enough to avoid a wreck.

Who is most likely to drive distracted?

Many teens — and some adults — make poor choices while behind the wheel. Which people are more likely to do something like text, talk or eat while driving? That may come down to personality, a new study finds.

Despina Stavrinos is a psychologist at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. She probes what causes car crashes. Her lab teamed up with researchers at Pennsylvania State University in University Park to home in on the role of personality in distracted driving.

The researchers recruited 48 licensed teen drivers, all 16 to 19 years old. Each completed a survey that asked about their use of smartphones while driving. The questions asked how often the participants had texted while driving in the last week. Or talked on the phone. Or interacted with their phones in other ways, such as reading social media posts or other news. The teens also took the Big Five personality test.

The Big Five breaks personality down into five main areas: how open they are, how conscientious, how extraverted, how agreeable and how neurotic. People high on the openness scale are willing to try new and different things. Conscientious people follow through when they say they will. Extraverts are outgoing and like to spend time with others. Agreeable people are considerate of others. Neurotic people tend to be worriers.

The researchers expected to find that extraverts and people who are open and agreeable would be most likely to text, talk or otherwise use their phones while driving. In fact, openness was related to texting. Teens who scored high on this scale texted while driving more often than others did. Extraverts were more likely to talk, not text, on their phones.

The study also turned up two big surprises. More agreeable teens rarely talked or texted while driving. They used their phones while driving less than any other personality group. The second surprise: Conscientious teens were just as likely as open teens to both text and use their phones for other activities, such as checking social media.

Agreeable people “may be more likely to display cooperative, safety-relevant behaviors,” Stavrinos speculates. As a result, she notes, they may be more likely to follow the rules of the road. “On the other hand, conscientious individuals may value social interactions with peers more than road safety.” These teens feel the need to stay in contact with their friends, even while driving.

Driving safely with friends

“Teens should know that even their ‘conscientious’ friends may be distracted drivers,” Stavrinos says. “No one seems to be ‘immune’ to distracted driving.” She suggests that teens find ways to stay socially connected — just not while driving. “For example, some cell phone providers will send automated texts to people for you while you are driving,” she says. But, she notes, the best practice is just to not interact with your phone at all when you’re behind the wheel.

Klauer agrees. Teens need to keep their eyes on the road in front of them, she says. Not doing so puts both the driver and other people in danger. Teens should put their phone someplace where they can’t reach it while driving, she recommends. After all, she observes: “No message is that important that it can’t wait.”