Why are cicadas such clumsy fliers?

Chemical analysis of the insects’ wings by a teen and his dad now offers clues

Periodical cicadas spend most of their life underground, sucking sap out of tree roots. Once every 13 or 17 years, they all emerge from the ground to mate and then die.

USDAgov

Cicadas are great at clinging to tree trunks and making loud screeching sounds by vibrating their bodies. But these bulky, red-eyed insects aren’t so great at flying. The reason why may lie in the chemistry of their wings, a new study shows.

One of the researchers behind this new finding was high-school student John Gullion. Watching cicadas on trees in his backyard, he noticed that the insects didn’t fly much. And when they did, they often bumped into things. John wondered why these fliers were so clumsy.

“I thought maybe there was something about the structure of the wing that could help explain it,” says John. Luckily, he knew a scientist who could help him explore this idea — his dad, Terry.

Terry Gullion is a physical chemist at West Virginia University in Morgantown. Physical chemists study how a material’s chemical building blocks affect its physical properties. These are “things like a material’s stiffness or flexibility,” he explains.

Together, the Gullions studied the chemical components of a cicada’s wing. Some of the molecules they found there may affect wing structure, they say. And that might explain how the insects fly.

From backyard to lab

Certain cicadas, known as periodical types, spend most of their lives underground. There, they feed on sap from tree roots. Once every 13 or 17 years, they emerge from the ground as a massive group called a brood. Groups of cicadas gather on tree trunks, make shrill calls, mate and then die.

John found his study subjects close to home. He collected dead cicadas from his backyard deck in the summer of 2016. There were plenty to choose from, because 2016 was a brood year for 17-year periodical cicadas in West Virginia.

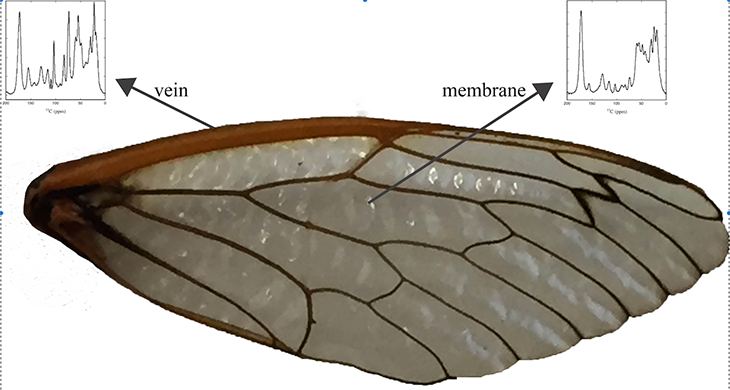

He took the bug carcasses to his dad’s laboratory. There, John carefully dissected each wing into two parts: the membrane and the veins.

The membrane is the thin, clear part of the insect wing. It makes up most of the wing’s surface area. The membrane is bendable. It gives the wing flexibility.

Veins, though, are rigid. They’re the dark, branching lines that run through the membrane. Veins support the wing like rafters holding up the roof of a house. The veins are filled with insect blood, known as hemolymph (HE-moh-limf). They also give the wing cells the nutrients needed for them to stay healthy.

John wanted to compare the molecules making up the wing membrane to the those of the veins. To do this, he and his dad used a technique called solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMRS for short). Different molecules store different amounts of energy in their chemical bonds. Solid-state NMRS can tell scientists what molecules are present based on the energy stored in those bonds. This let the Gullions analyze the chemical makeup of the two wing parts.

The two parts contained different types of protein, they found. Both parts, they showed, also contained a strong, fibrous substance called chitin (KY-tin). Chitin is part of the exoskeleton, or hard outer shell, of some insects, spiders and crustaceans. The Gullions found it in both the veins and the membrane of the cicada wing. But the veins had far more of it.

Story continues below image.

Heavy wings, clunky fliers

The Gullions wanted to know how the chemical profile of the cicada wing compares to that of other insects. They looked at a previous study on the chemistry of locust wings. Locusts are more nimble fliers than cicadas. Swarms of locusts can travel up to 130 kilometers (80 miles) a day!

Compared to the cicada, locust wings have almost no chitin. That makes locust wings much lighter weight. The Gullions think the difference in chitin could help explain why light-winged locusts fly farther than heavy-winged cicadas.

They published their findings August 17 in the Journal of Physical Chemistry B.

The new study improves our basic knowledge of the natural world, says Greg Watson. He’s a physical chemist at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Queensland, Australia. He wasn’t involved in the cicada study.

Such research may help guide scientists who are designing new materials. They need to know how the chemistry of a material will affect its physical properties, he says.

Terry Gullion agrees. “If we understand how nature is done, we can learn how to make manmade materials that mimic the natural ones,” he says.Terry Gullion agrees. “If we understand how nature is done, we can learn how to make manmade materials that mimic the natural ones,” he says.

John describes his first experience working in a lab as “unscripted.” In the classroom, you learn about what scientists already know, he explains. But in the laboratory you get to explore the unknown yourself.

John is now a freshman at Rice University in Houston, Texas. He encourages other high-school students to get involved with scientific research.

He recommends that teens who are really interested in science should “go and talk to someone in that field at your local university.”

His dad agrees. “Many scientists are open to the idea of high-school students participating in the lab.”